My friend and mentor Arthur J. Finkelstein died last night. If you’ve never heard of him, that’s how he wanted it.

The son of Belarusian immigrants, Arthur was born in the 1940s and grew up in Brooklyn. He was a mathematical savant, and went to Columbia University. He crossed paths with Ayn Rand, and at one point in his young life was a collaborator on her radio show in New York City.

In his early 20s, Arthur was hired as a data analyst for the Nixon Administration. By 1972, he was producing commercials for Nixon’s reelection campaign. He went on to consult for the likes of Strom Thurmond, Jesse Helms, Alphonse D’Amato, George Pataki and Ronald Reagan, merging his ability to gather and analyze data at an astonishing pace with his sharply creative mind. At one point in the mid-1990s, a significant plurality of United States senators were Arthur’s clients. He only worked for Republicans. Overseas, he worked for Ariel Sharon and Binyamin Netanyahu. He consulted for prime ministers and presidents all over Europe.

Because Arthur couldn’t be everywhere, he made a practice of discovering and cultivating young talent. He sent me to the Czech Republic for months to work in a national race, and to Nigeria for a week during that country’s tumultuous 2015 presidential campaign. He sent one of my friends to Kosovo before Kosovo was even a country – and my friend stayed for four years, advising the fledgling government with Arthur’s remote guidance.

CNN once called Arthur the “Kaiser Soze of American politics,” referencing the shadowy, never-seen crime boss in The Usual Suspects. Some people, it was reported, didn’t think Arthur even existed, but that his name was a bogeyman invoked to scare liberal opponents. I laughed when I read that, having had dinner with Arthur in New Orleans only a week earlier. He existed. He definitely existed, larger than life to those who knew him, and nobody at all to the public at large. I’ll admit to a sort of sardonic pleasure when I was with Arthur in public, thinking to myself, “Nobody knows who this man is, but he has done so much to impact their lives.”

Arthur was kind, brilliant, sly, unassuming and hilarious. He didn’t just employ me on occasion, but he was my friend. He rarely called, but often emailed – often random messages like, “Happy Friday!” or “Good morning! Hope you’re well.” He began every conversation with, “good morning!”, regardless of the actual time of day; I attributed it to the fact that he was constantly changing time zones in his travels and work.

He alternated between horrible eating habits and hardcore dieting. I sat in lunch meetings with him where he ate nothing but slices of swiss cheese, and once had dinner with him at an outdoor café in Prague, watching him eat a raw onion dipped in fondue.

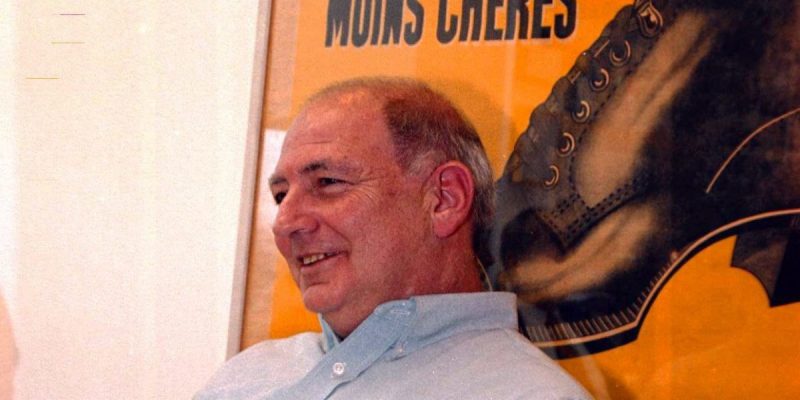

He rarely (if ever) dressed formally. He traveled the world with a carryon bag, and I don’t think I ever saw him in anything but khakis, a blue button-down shirt and, occasionally, a navy blazer. He wore only loafers, which he took off unabashedly as he paced a room giving lectures on poll data, dictating a press release, or laying out a strategy. He once told me that after an extended meeting with President Reagan and James Baker in the Oval Office, he received a letter from Baker: “Dear Mr. Finkelstein: Thank you for meeting with me and the President last week, and thank you for keeping your shoes on most of the time.”

Arthur didn’t like technology. He didn’t have a laptop, but only a Blackberry. He kept his campaign plans scrawled in pencil on pages torn from a legal pad, which he carried in his breast pocket. He and I once had a somewhat furtive meeting with a world leader at a restaurant in a remote village near the Czech-Austrian border. When he asked me for the poll data, I pulled out my laptop and opened it. He looked at me like I was an idiot and asked where the actual BINDER of poll information was. It was hidden in a safe place in my hotel, but he would have preferred paper.

Arthur rarely worked for candidates in races that were smaller than statewide or national, but he made exceptions for friends, including California Congresswoman Mary Bono Mack and Florida Congressman Connie Mack. (He sent one of my associates to work on Mary’s campaign for a full 14 months; he asked me to go work full-time for Connie in 2010, leading up to Connie’s Senate run, and I declined; although I rarely said no to a request from Arthur, it turns out that was a good call on my part.)

Advertisement

When the Washington Post first reported that he was gay in the 1990s, Arthur was irked – not because he was ashamed, but because it was nobody’s business. He wasn’t a celebrity or public figure, and he didn’t want to be. Hillary Clinton made some snarky comments about him when that story broke, and he never forgave her. When she was first gearing up to run for president, Arthur launched a website called StopHerNow.com, dedicated just to her.

One of my former associates once emailed me that while taking a graduate course he was assigned a chapter to present to the class. It was called, “The Most Evil Man in America,” and it was about Arthur. I asked Clifton if he told the professor he actually knew the Evil Man in question; he replied that he hadn’t, and wasn’t going to until the semester was over. Arthur was not evil, although Mrs. Clinton and a bevy of other Democrats would disagree with me.

Arthur was intensely private. He didn’t grant interviews. He didn’t like to be photographed. He didn’t like being in the news. When then-GOProud Executive Director Jimmy LaSalvia sent an angry tweet that referred to presidential candidate Rick Perry’s pollster as a “faggot,” it became news – and some media linked the pollster in question to Arthur because they had worked on the same campaign once, more than 20 years earlier. Arthur was livid. He called me to vent, in part because I had arranged for he and LaSalvia to meet in Boston only a few months earlier.

Arthur and his husband Donald were together for 50 years, and had children and grandchildren. Donald, a teacher, held down the family front while Arthur traveled, changing the world.

That is what he did, you see: He changed the world. Without fanfare, without drawing attention to himself, without a spotlight, Arthur worked hard to elect good people to high office. Excluding some candidates and office-holders, it’s impossible to think of a single person who has had as much impact on American politics – and, indeed, global politics – as did my friend Arthur. Excluding very few, it’s hard to think of a single person who has had such an impact on me, on my life and career.

The Kaiser Soze of American politics, the Most Evil Man in America, arguably the most impactful man in modern politics, has gone on to the next life. I will miss him. I already do. Many in the world will feel the loss, without noticing or even knowing about it. Arthur’s legacy is vast and important, and invisible to most.

That’s how he wanted it.

Advertisement

Advertisement