The Take ‘Em Down NOLA movement ignores unpopular historical facts while leading its removalist campaign. The group crusades against slave owners and people connected to the short-lived Confederate States of America, but it has long avoided the reality that Black people owned Black slaves and Blacks were part of the Confederacy. As complex as that past may be to some, New Orleans, Louisiana, has an even more convoluted history. And some of the Black heroes, honored with memorials, meet Take Em Down’s qualifications for removal.

Louisiana led all states in Black slave ownership, and it was not even close. The 1830 United States census showed that 965 Louisiana Blacks owned 4,206 slaves. According to that census, Louisiana had 25% of the total number of “free Black slave owners” in America and 33% of the total number of “slaves owned by free Blacks” in America. The next highest in each category were Virginia with 948 Blacks owning 2,235 slaves and South Carolina with 464 Blacks owning 2,715 slaves. The New Orleans population was 46,082 in 1830, and locally 753 Blacks owned 2,349 slaves in the Crescent City.

Thirty years later, the number of Black slave owners had quadrupled. According to federal census reports, on June 1, 1860, New Orleans had 10,689 non-slave Black residents, or free people of color as was a phrase of the era. Of those “over 3,000 free Negroes owned slaves, or 28 percent of the free Negroes in that city,” according to Duke University professor John Hope Franklin, America’s leading African American historian.

Take ‘Em Down NOLA has never addressed Black ownership of other Blacks. Nor have its members discussed the impact of segregation on the mixed-race Creoles of Louisiana. Yet those issues play a part in the histories of some well-known Black New Orleanians from the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Author Tom Sancton wrote about the Creole Black population’s opposition to segregation in his 2006 memoir, Song For My Fathers. The book contains insightful quotes regarding the now monumental civil rights Plessy vs. Ferguson U.S. Supreme Court case of 1896, but also contains the little discussed motivation of Black Creole Homer Plessy.

In the nonfiction book, Antoine Plessy, Homer Plessy’s cousin, discussed Homer’s father and grandfather. Their original name was du Plessis. A major revelation was “The grandfather, in fact, had been a wealthy free man of color who owned slaves, ‘threw his lot in with the Confederacy,’ and was wiped out by the collapse of Confederate money.”

Sancton quoted Antoine Plessy stating, “Homer felt superior to the American-speaking colored because they had been slaves and were from a lower social level than him. See all the Creole families thought they were better than the ex-slaves. And to keep from going with these people—you know, there was prejudice—they established their own social clubs and dance halls all through the city. … Sometimes you would go in those places when they were holdin’ a soiree and you wouldn’t see a dark face. Well, they done that purposefully.”

Sancton quoted noted civil rights attorney Alexander Pierre “A.P.” Tureaud saying, “There was a certain amount of pride that these Creoles had in their ancestry. They wanted to make a distinction between them and the slaves. They were a stratified group of their own.”

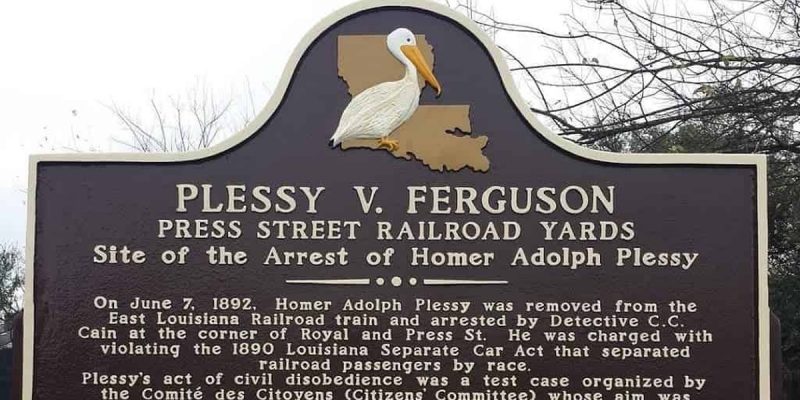

Sancton wrote about his research including the “comite des citoyens” which famously set up the scenario in which Homer Plessy was arrested in 1892 in violation of the Separate Car Act. Sancton wrote that the committee was made up of mixed-race Black Creoles who tried “to wall themselves off from the Blacks.” According to the author and his subjects, the comite des citoyens’ motivation was that “they didn’t want to be thrown into the Jim Crow car with the dark-skinned ex-slaves. They themselves were anything but ‘color blind.’ They were in fact fighting for a kind of segregation—the right to maintain their own separate social status. They lost that fight and were forced to cohabit, despite their own prejudice and pride, with the darker, rougher population.”

It should be noted Song for My Fathers has a cover endorsement quote from New York resident Wynton Marsalis, the ex-pat New Orleanian who guilted Mitch Landrieu into initiating the removal of the revered General Robert E. Lee monument from Lee Circle.

Other New Orleans historical facts disrupt the pop culture “Civil War” narrative. More than one-out-of-four Black New Orleanians owned Black people the year before the War for Southern Independence began. In late 1860, an anonymous group of Black Louisianians penned and submitted a letter that was published in the Delta newspaper. The letter was signed “A Large Number of Them” and consisted in part of the following:

“The free colored population (native) of Louisiana … they love their home, their property, they own slaves, and they are dearly attached to their native land, and they recognise no other country than Louisiana, and care for no other than Louisiana, and they are ready to shed their blood for her defense. They have no sympathy for abolitionism; no love for the North, but they have plenty for Louisiana, and let the hour come, and they will be worthy sons of Louisiana. They will fight for her in 1861 as they fought in 1814-‘15.”

Louisiana seceded from the United States on January 26, 1861. When Governor Thomas O. Moore requested organizing troops, the “1st Louisiana Native Guards” volunteer regiment was formed. In April 1861 the military unit consisted of 1,500 native Louisiana Blacks—some from prominent Black families, others working class free Blacks. The Native Guards did not battle, and when the Union sacked New Orleans in April 1862, approximately 10% switched their allegiance from the Confederate State of Louisiana to the United State of Louisiana. Among those were André Cailloux, the Confederate turned Union officer, and Morris W. Morris, the only Black Jewish officer to serve in both the Confederate and Union armies during The War Between The States.

One member of the Native Guards was, as records spell the name, private Adolph Plessir. Homer Plessy’s surname derives from Du Plessis and his father went by the first name Adolph. The National Parks Service’s war records frequently have typos and misspellings, so technically Adolph Plessy’s Confederate military service is unconfirmed. These records also show private E. Duplessis in the 1st LA Native Guards as well as captain E. Plessis in the “4th Regiment, French Brigade, Louisiana Militia.” So in addition to Homer Plessy having a slave-owning Confederate grandfather named Du Plessis, possibly the E. Plessis, his father Adolph Plessy likely volunteered as a private in the Confederate regiment of free Blacks in New Orleans.

Many contend the War of 1861-65 was singularly about Southerners fighting to maintain slavery. Using that argument and reading about Black people siding with the Confederacy, history shows Black people volunteered to battle to perpetuate the institution of slavery. And it wasn’t just in Louisiana. This Abbeville Institute article compiles newspaper articles about Black Confederates in nearly every Southern state. If one wants to know about actual events of the past, Google is not an adequate research source. Historical documentation exists, but finding it takes more skill and effort than typing in a web browser.

Advertisement

Technically, Take Em Down’s central goal has been to “Take down all symbols of white supremacy.” On the surface, the Black Creole pride could be argued as a form of Black Supremacy, superiority over other Black people. But Plessy considered himself an “octoroon” claiming to be 7/8 White, 1/8 Black. Plessy was genetically mixed Black and White, meaning his prejudice against African Blacks was in reality a White blooded person defending his believed superiority over Black skinned Blacks—or White supremacy.

It can also be argued that the Creole mixed-race supremacy was a form of colonial White supremacy, with a twist. When the French cash crop colony of Saint-Domingue was overthrown in slave revolts, many Blacks, Whites, and mixed-race people relocated to New Orleans. Saint-Domingue, or Haiti, had a race-based caste system with 128 combinations of White-Black admixtures. This system had more commonly known classifications such as quadroon and octoroon, while others–less well known or referenced–existed such as affranchise, sacatra, Marabous, and griffe. The system practiced in Haiti was carried to New Orleans. And in the late 19th century, government-imposed segregation put an end to the mixed-race spectrum because it divided people along one singular racial axis, identifying them as either Black or White.

This is history. Today, it may seem superficial, judgmental, derogatory, and as prejudicially racist as something can be, however it was part of integrated coexistence between Europeans and Africans in the new world in the 18th and 19th centuries. The genealogical admixtures were used to establish a caste hierarchy which should never have existed. Hence why it’s gone. However, it’s history, and no one has to like it. Awareness, though, can help the human race positively evolve.

Take Em Down’s list of targets for renaming/removal has only attacked White historical figures. Homer Plessy’s racial supremacy undoubtedly places him on the list of those oppressing Blacks in New Orleans. Moon Landrieu’s complicit denial of his African ancestry, slave owning heritage, and heritage as a descendant of a Confederate soldier qualifies him for the removal list as well. The Treme neighborhood is named for Claude Treme, a man who seized slaves belonging to another man, and was also documented murdering at least one slave.

But with Take Em Down making exceptions for Landrieu, Plessy, and Treme, they are allowing systemic White supremacy to carry on. Take Em Down’s silence on Treme implies that the group wants the prominent neighborhood name to remain, forcing residents of Treme to live in a neighborhood whose name reveres a slave owner and slave murderer. And citizens and tourists who stroll along the Moon Walk do so along a city-owned path named for a man whose family covertly exploited its European heritage over its Black heritage, and whose family also owned slaves and fought for the Confederacy. Plessy is New Orleans’ primary civil rights figure and his legacy is commemorated with a landmark and “Homer Plessy Way.” Tureaud spoke of mixed-race supremacy, so who knows if that still condemns him in the lens of Take Em Down, but he is commemorated with a statue and “A. P. Tureaud Avenue.”

Interestingly, the A.P. Tureaud Legacy Committee promotes #StreetSignsMatter, described as “a movement to erase our streets of figures in history who fought to enslave and oppress Black people.”

Take Em Down ignores facts like the prevalent New Orleans practice of Blacks owning Blacks, mixed-race superiority & Black Confederates. Take Em Down chooses to remain ignorant and inconsistent because these historical truths do not fit their narrative or advance their agenda.

Marxists like the Take Em Down group want to destroy history to rewrite the past their way. And if the city of New Orleans continues to erase the true history of New Orleans, the anarchists will be able to rewrite history. It began by removing monuments to Confederate leaders and a local militia overthrowing the Reconstruction government. Now they want to remove colonial governors’ names from streets, and any other names or historical references they dislike.

The anarchists want to fix it so they get to make the decisions. For some reason, the American public has taken a back seat on the ride, allowing one side to make all decisions as to what public art and property is acceptable or unacceptable, with no balance and no concern for New Orleans’ local, complicated, multi-colored history.

Take Em Down’s agenda is flawed, hypocritical, inconsistent, and manipulated to their wants. In short, they are frauds.

Advertisement

Advertisement