Anticipated federal policy changes to oil and gas leasing and permitting on federal lands “could shift oil production, prompting a realignment of Permian Basin activity between Texas and New Mexico,” a new report by the Dallas Fed says.

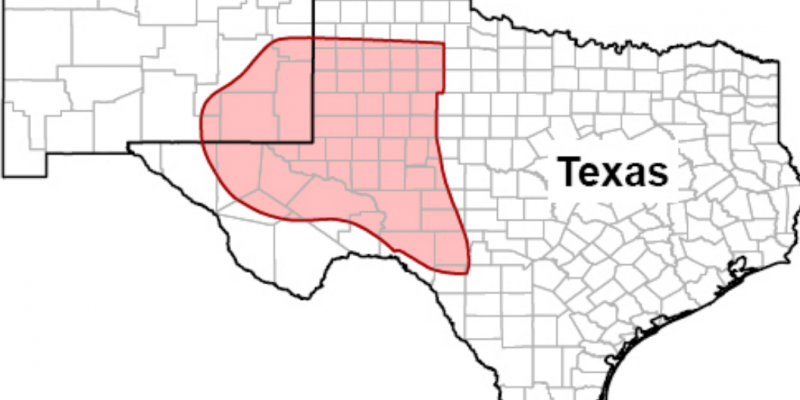

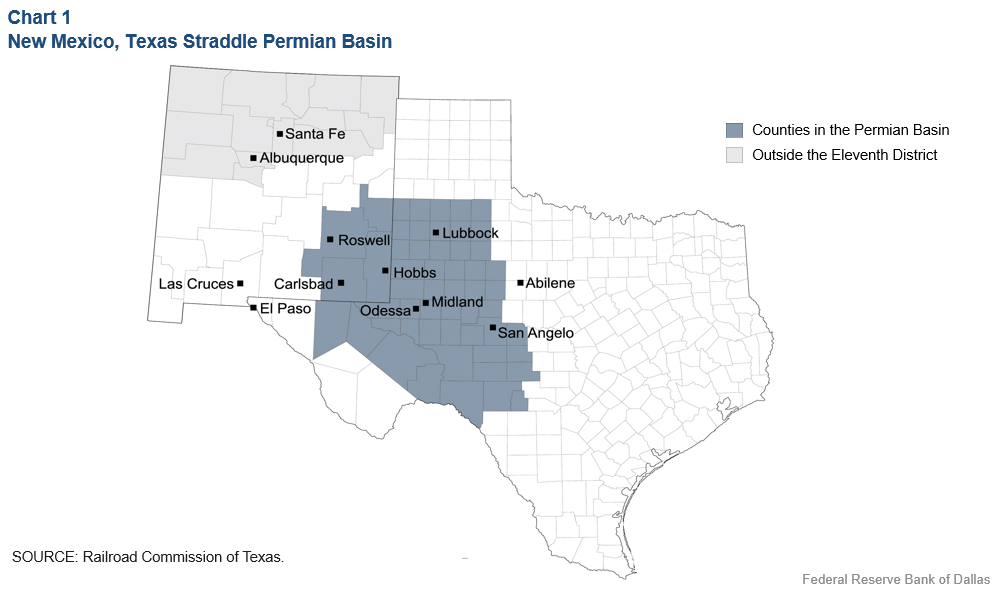

The Permian Basin is the world’s largest shale oil and gas field, located in the Dallas Fed’s Eleventh District service area, straddling the Texas-New Mexican borders.

On the New Mexico side, half of the oil and gas produced in the Permian Basin occurs on federal land. On average, even during the state’s shutdown in 2020, the state produced 1 million barrels of oil per day. On the Texas side, roughly 3 million barrels of oil were produced daily, but on private and state-owned land.

Economists Garrett Golding and Kunal Patel estimate that by the end of 2025, the Permian Basin will produce between 230,000 and 490,000 barrels per day less than if drilling activity continued at its current pace. They write that the impact on New Mexico of President Joe Biden’s energy policies “would slow economic growth, adversely affecting that state’s employment and tax collections.”

In a recent letter to the Biden administration, New Mexico Energy Secretary Sarah Cottrell Propst wrote something similar in her request for a waiver from one of Biden’s executive orders halting new oil and gas leasing on federal lands. She wrote the order “has resulted in on-the-ground uncertainties that undermine our ability to safeguard New Mexico’s economy and environment.

“Approximately 55% of oil and gas wells in New Mexico are drilled on federal lands, particularly in the Permian Basin. By contrast, the Texas side of the Permian Basin is largely private land and therefore unimpacted by the new federal actions. We have seen rigs depart New Mexico for Texas simply because of the uncertainty caused by the Order.”

As a result, the Dallas Fed notes, “production and employment across the basin will gradually shift from federal lands in New Mexico to private and state lands in New Mexico and Texas, with wide-ranging economic implications for the region.”

To drill for oil on federal land in New Mexico, companies generally lease acreage from the Bureau of Land Management for 10-year periods and apply for permits to drill wells. Permits are valid for two years. If they go unused, leaseholders can obtain a two-year extension.

By contrast, in Texas, private leases extend for 3 to 5 years, and permits to drill are filed with the Texas Railroad Commission.

Based on media reports and discussions with stakeholders, the economists considered two scenarios to evaluate the impacts of Biden’s policy changes in the Permian Basin assuming an average $50 West Texas Intermediate benchmark and that little changes would occur related to leasing, permitting and drilling from first-quarter 2021 levels.

In the first scenario, assuming there is no new federal leasing, but existing leaseholders continue receiving drilling permits, New Mexico’s production would grow slightly from 1 million barrels per day to 1.5 million barrels per day.

If permit reviews are more rigorous, approvals are slower and operations are costlier in 2022, “firms that hold acreage across the basin gradually relocate drilling rigs and completion crews to their nonfederal locations,” the report forecasts.

The second scenario evaluates what would happen if no new federal permits or extensions are granted starting in 2023, when the most recently issued permits are slated to expire.

“The existing permitting freeze adversely affects production in the near-term due to a lack of approvals of permit modifications and pipeline rights-of-way,” the report states. New Mexico’s output would then drop to 700,000 barrels per day and “an expected employment shift in drilling will take place from New Mexico to Texas.”

The analysis estimates that between 3,500 and 6,600 drilling and completions workers would lose their jobs in New Mexico from now through 2025. Texas would gain, or need, an additional 5,400 and 7,400 workers.

The shift in employment in the oil and gas industry impacts a range of industries, extending “to support and corporate jobs, with secondary effects on local retail and hospitality sectors” and will put “a large and growing portion of state revenue at risk after this year,” the report states.

One-third of New Mexico’s general fund comes from taxes, royalties and fees paid by the oil and gas industry. In fiscal year 2020, this totaled $2.6 billion; $809 million came from mineral revenues on federal land.

Biden policies in New Mexico will also have a reverberating effect, impacting refineries and chemical facilities on the Gulf Coast that will need to adapt to loss of barrels coming in from the Permian Basin. These refineries and chemical facilities expanded operations in recent years to increase capacity and be able to process a range of light and super-light crude oil produced in the Permian.

They will also impact the global market, meaning Americans and others will be forced to rely on foreign oil instead of oil produced in New Mexico or Texas.

“Oil from West Africa and the Arabian Gulf could most easily substitute for the lost inputs,” the authors note. “Suppliers in those regions could also replace Permian volumes previously destined for the export market – primarily to East Asia and South America.”

“We expect production from other basins to decline against business-as-usual forecasts as well, especially in the Gulf of Mexico, where the federal government manages nearly all oil and gas activity,” the authors write.

Advertisement

Advertisement