Editor’s note: This entry was originally published on Oct 11, 2017 as part of my work towards an MA in History at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. My days pouring over primary documents in the Special Collections room in the library was one of the most fruitful and frightening times in my lifelong acquisition of knowledge. It is truly mind-numbing to consider how much real history never makes it to government controlled textbooks.

I was going to revise it to fit today, Memorial Day 2024, but I decided to leave it as is to better connect to future posts on a most fascinating topic I chose to research–the largely unknown POW camps in Louisiana during World War II and how politics and economics, not to mention a number of captured Italians stealing wives from men fighting overseas, played a role in the sugarcane industry. It is an industry my father spent his life working in.

—

Some stories are told so many times they lose their truth. And some aren’t told nearly enough.

World War II is a popular subject among those inside and outside the university setting. Unfortunately, however, there are only certain images that come to most individuals’ minds when the subject is mentioned. The Pearl Harbor attack, the D-Day invasion, and the dropping of two atomic bombs on Japan are perhaps the three most recognizable.

The more these parts of the story are told, the more they do one of two things: 1) get aggrandized and lifted into the realm of myth and over-glorification, or 2) get nitpicked to such an exhaustive degree that they lose their value and context. The one can make America look super-heroic; the other can paint it in the light of pure villainy. Of course I provide two extremes here to make a point; to be fair, there are other shades in the middle. Still, with our hyper-political culture and ever-widening dichotomy down the political aisle, the notion of such a stark binary is not completely out of the realm of reality. People often view history through the political lens of the present.

This project, tentatively titled “One Important Story: Life and Labor in the Louisiana Prisoner of War Camps,” is my humble contribution to solving this tendency to clump World War II into big chunks that are too simple and easily misrepresented. Many people I talk to are surprised to hear that the United States housed POWs during World War II. Their question is inevitably, why? One reason is a simple answer involving the shortage of field labor in America and looming harvest failures and food shortage. There are other reasons, of course, but such simplicity should show how many moving and tenuous parts were grinding during the war–and how little too many of us recognize our good fortune that the machine didn’t break entirely. Moreover, it turns out that this story of the prisoners of war entails so much more than the practical service they provided.

The prisoners that came over–of Italian, Japanese, and German descent–were real live human beings that had interests and personalities just like anyone else. They also harbored their own politics. It is something many Americans have to reconfigure in their minds, once they get passed the idea of prisoners of war being here in the first place. Not every German was a Nazi sympathizer. Not every German was anti-Nazi.

Some simply didn’t care and had gotten tossed into the war by the draft.

When not working, POWs passed their time playing sports, playing chess, writing plays, singing songs, making sculptures, painting art, building monuments, and creating gifts for the officers in charge of them and their families. They were frequently entrusted with gun patrol duty–over their own fellow prisoners–so the American guards could handle some pressing business or go to a Christmas party. They missed their loved ones. They wanted to go home. They cried. Even though on the whole many of them made lasting friendships here.

Advertisement

In this project, I will attempt to show several simultaneous dynamics surrounding the prisoner of war program, for the primary reason of illustrating that history is not as simple as our biases and politics would have us believe. I must, however, plan for three goal levels and work my way through each one. This will allow me the option to stop more strategically if the final deadline looms and I haven’t reached my stretch goal.

My ultimate stretch goal is ambitious–to provide an attractive and content-heavy archive, using a series of photographs, documents, and original copy, of 1) the politics involved in the heated exchanges between congressmen, military personnel, and desperate farmers; 2) the prisoner culture created in the camp through art, letters, and music; and 3) the story of one prisoner, K. Herbert, and his journey through several Louisiana camps.

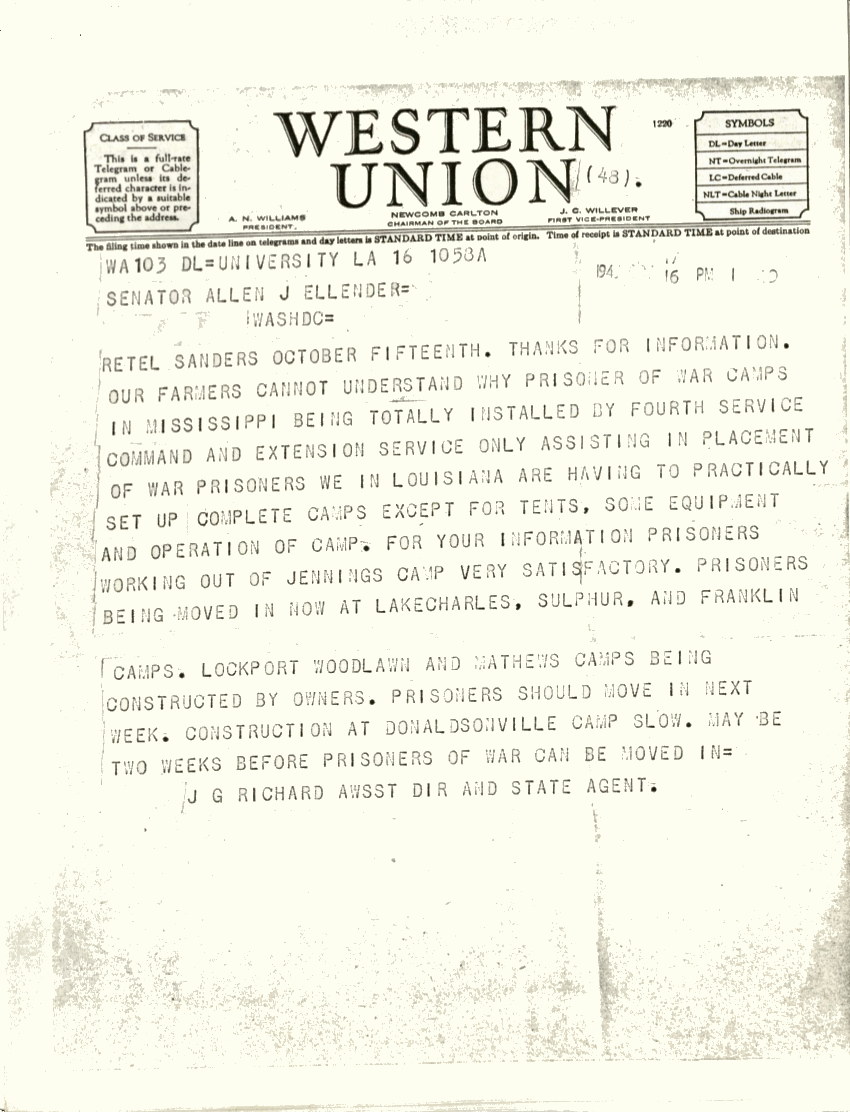

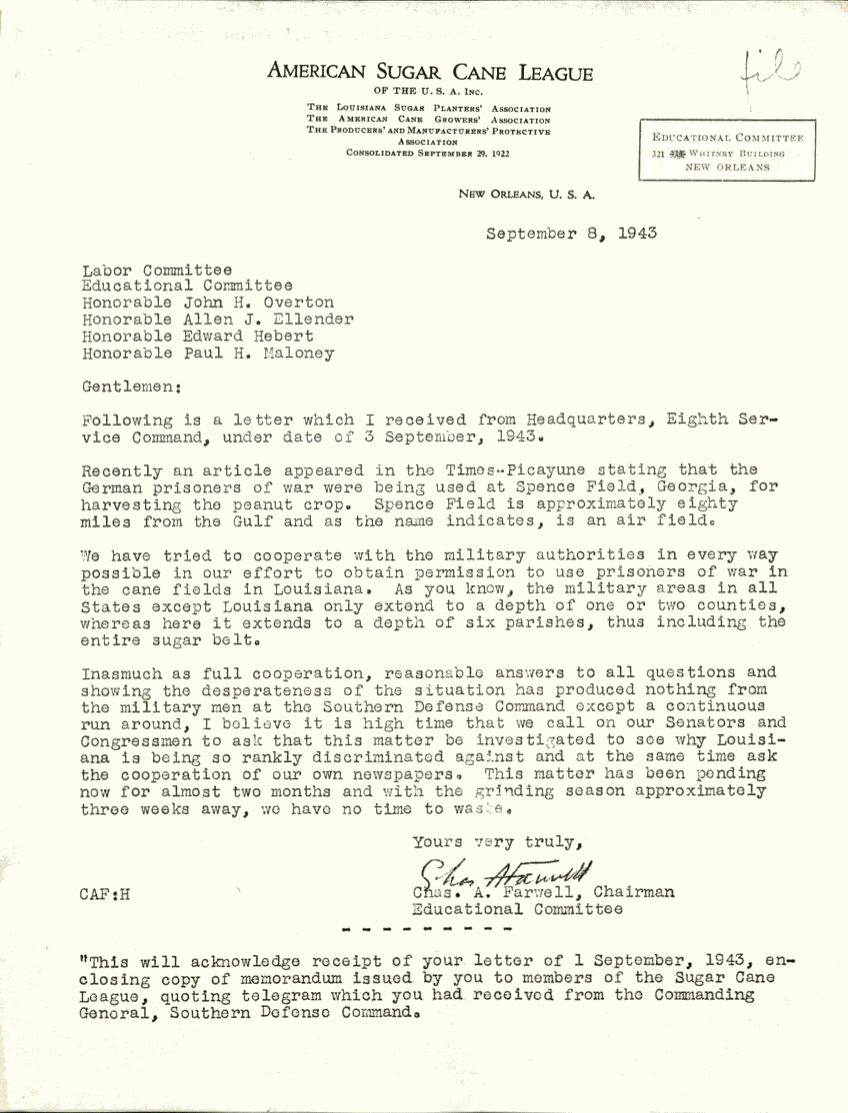

Here are just two examples of the correspondence:

My plan is to work through K. Herbert first, then through the POW culture as a whole, then through the politics puppeteering the prisoners involved. It seems to me that there is enough material on just K. Herbert to create a thorough and intriguing school project, and if my sole purpose was simply to be done with it at semester’s end, I would start and end there with my vision.

However, my plan is to cultivate this project over the long term, so my decision to stop at one of the preliminary levels would be temporary. My desire to implement Omeka, WordPress, and other programs into my overall online portfolio, of which this current project will be a crucial part, is an indication of my desire to continue the research and work on this topic long after the semester ends. Because the World War II museum in New Orleans is on my list of possible job sites when I graduate, and I would like to tap into their already prodigious audience base, I want to spend the interim fleshing out a nuanced historical look at as many aspects of the war as I can. This project, on one of those most important stories rarely told, is one piece of that.

Advertisement

Advertisement