For one party attached to Louisiana’s ongoing controversy about its congressional districts, it’s a matter of forcing a smile and hoping for the best.

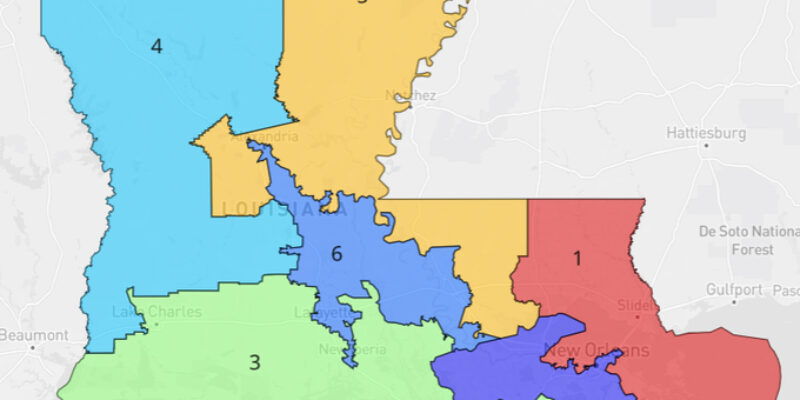

Last week, the losers of Callais v. Landry turned in petitions to the U.S. Supreme Court about whether sufficient cause existed for the Court to take up the case directly. Earlier this year, a three-judge panel ruled the state’s redone map impermissibly used race to draw a two majority-minority district map, inflating beyond constitutional bounds that use at the expense of ignoring equal protection of voters and traditional principles of reapportionment.

That plan had come about after another was enjoined by another district judge prior to any trial ruling the drawing of such a map violated the Voting Rights Act by only including a single M/M district. This was unprecedented, as no court ever had endorsed drawing boundaries specifying that the proportion of M/M districts had to equal that of the state’s population, much less without a trial on the merits, on the basis of the VRA which itself explicitly rejects that approach except in cases of clear intent to deprive minority group members of voting rights.

So, the losing parties to Callais were asked to submit why they think the Court should hash all this out, to be followed by the winning party a month later. One of the losers, the state, officially said it just wanted clarity on the criteria involved while the other, a collection of special interests who technically weren’t on the losing side but who were granted limited privileges in defending the abrogated second attempt, argued it wasn’t so much as finding the correct balance as the panel’s ruling was a misapplication of the district court’s ruling.

And, to their credit, they try make lemonade out of the lemon they received not long after Callais was decided. That came in the form of Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference, which essentially delinked constitutional questions from masquerading for their political goals, which was to increase the numbers of Democrats in Congress. The Court said that a congressional map that otherwise didn’t violate traditional principles of reapportionment, such as compactness and contiguity of districts, did not have to have the proportion of M/M districts somewhat equivalent to the proportion of minority race residents in the state if the legislature wished to draw districts to maximize partisan advantage even if incidentally related to racial division in voting.

Thus, and ironically, the first map tossed by the district court likely would have been salvaged under the ambit of the Alexander ruling. With a certain degree of chutzpah, the special interests on the short end of the Callais stick contend Alexander helps then, because in their rendition the Legislature had political reasons for drawing districts as it did to protect certain incumbents at the expense of another.

Except that the facts established at the trial clearly showed legislators drew the map because they felt, far and beyond any other consideration, that they had to create a second M/M district. Probably understanding this gaping hole, the special interests fall back to another tactic: that the map drawn violated worse the traditional principles than alternative maps that could be two M/M. But this is like saying one pregnant woman is less in the family way than another; it doesn’t matter the degree to which race was used absent any compelling reason under strict scrutiny in drawing boundaries, but that it was.

This has left those interests whistling past the graveyard in asking for Court review, especially as the winning plaintiffs likely will frame their response accepting the invitation of Assoc. Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s concurrence in the operative case upon which the district court had relied (which, pointedly, didn’t end up ordering a proportional solution to Alabama’s map and after a full trial), that questioned whether the VRA’s defining the way race could be used in reapportionment had outlived its usefulness. That showed Court willingness to expand this to a constitutional question beyond statute and an extreme likelihood of negating the entire approach used to invalidate the first map while confirming the second map’s infirmity.

Which would be fine by Louisiana. The Republican-led Legislature, as noted above, has made no secret it prefers a single M/M map, and whether the Court doesn’t intervene now or it does by declaring the stronger Callais decision operative, that gives it the green light to junk the current map and for 2026 put back in something like what the district court canceled, bolstered by Alexander. As for the special interests, they just have to hope that despite the signals the Court has been sending that they ultimately will lose that somehow doesn’t translate into a day of reckoning.

Advertisement

Advertisement