(Citizens for a New Louisiana) — Louisiana’s “Cleo District” has become the focal point of a Supreme Court case that could upend how redistricting is done across the country and restore or erase decades of racial gerrymandering precedent. While some states are scrambling to redraw maps ahead of the 2026 election, Louisiana leadership has been silent. They have not bowed to intense political pressure to do the same. That refusal is strategic. In Louisiana’s pivotal case, a high court decision could significantly reinterpret the Voting Rights Act or even declare that it violates the Constitution itself.

To understand how we arrived at this point — and why Louisiana might be the last stand for redistricting sanity — we need to rewind the clock to 1865.

Limited and Enumerated Powers

The U.S. Constitution is an agreement. It is a contract amongst the several states that outlines specifically delegated and enumerated powers to its agent, the federal government. Like any contract, it is binding only within the scope of the powers expressly granted and understood at the time of ratification. The states, as the original sovereign parties, never surrendered the entirety of their authority; instead, they delegated specific, enumerated, and limited functions—such as national defense and conducting foreign affairs—while reserving all other powers to themselves and the people, as affirmed in the Tenth Amendment.

As the federal government is merely an agent created by this compact, it possesses no legitimate authority beyond what the Constitution delegates. When it acts outside these bounds, it breaches the contract and infringes upon the sovereignty of the states. The enumerated powers doctrine serves as both a safeguard and a limitation, designed to ensure that the central government remains a servant rather than a master, thereby preserving the balance of federalism.

Changes to our form of government were rapidly accelerated following the American Civil War. If you exclude the Bill of Rights, between 1791 and 1865, only two amendments to the U.S. Constitution occurred: the Eleventh Amendment (1798) and the Twelfth Amendment (1804). The Thirteenth (1865), Fourteenth (1868), and Fifteenth (1870) were adopted under bayonet rule and through methods of coercion carried out against the defeated Southern states. The remaining twelve amendments were ratified between 1913 and 1992. Not counting the Equal Rights Amendment, which Biden falsely proclaimed had been ratified. Of the twelve amendments ratified between 1913 and 1992, five of them directly deal with elections.

Federal Government Encroachment

Over time, the federal government became more active in elections. The Fifteenth, Nineteenth, Twenty-Fourth, and Twenty-Sixth Amendments each carved out specific prohibitions on voter discrimination—by race, sex, poll tax, or age—and granted Congress the power to enforce these protections through appropriate legislation. This was not an open-ended transfer of authority, but a targeted expansion of federal jurisdiction over elections.

Modern voting rights law, including the Voting Rights Act, rests on this amended constitutional framework. While it may represent an exercise of delegated enforcement power, it must remain tethered to the specific constitutional guarantees it enforces. When federal action strays beyond the expressly delegated powers of the Constitution, it risks exceeding the scope of the agreement and altering the balance of power the states originally consented to.

It was under Democratic President Lyndon Johnson that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 were passed. Johnson openly acknowledged publicly that the Democratic Party might “lose the South for a generation”. At the same time, in private, he allegedly made statement(s) to the effect of, “I’ll have them n*****s voting Democratic for 200 years.” Over time, the Democratic Party did essentially lose the Conservative South. Those with a myopic view of history will simply say it was and is all racially motivated. Still, there has always been a struggle between the states and the central authority, with race being co-opted and weaponized to achieve political outcomes.

“OMG! You’re from the Sixties!”

There is a scene in the movie Field of Dreams where Ray Kinsella (played by Kevin Costner) shows up unannounced at the home of Terence Mann (played by James Earl Jones). Kinsella recites a line written by Mann. Mann responds:

“Oh my God! You’re from the sixties!” Kinsella smiles and confirms. Mann then picks up a handheld insecticide sprayer, pumping it and spraying it as he approaches Kinsella, stating: “OUT! Back to the 60’s! BACK! There is no place for you here in the future. Get back while you still can!”

The same could be said about the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Mann perceived in Ray a danger: living in the past blinds you to the present. Clinging to outdated enforcement structures or political narratives from the 1960s risks turning the Voting Rights Act into a blunt political weapon rather than a safeguard. If the law is to remain relevant, it must be grounded in the actual conditions of today’s elections, not the ghosts of half a century ago. Otherwise, we are simply reenacting a scene from a movie — swatting at phantoms, while the real challenges to election integrity and representation go unaddressed.

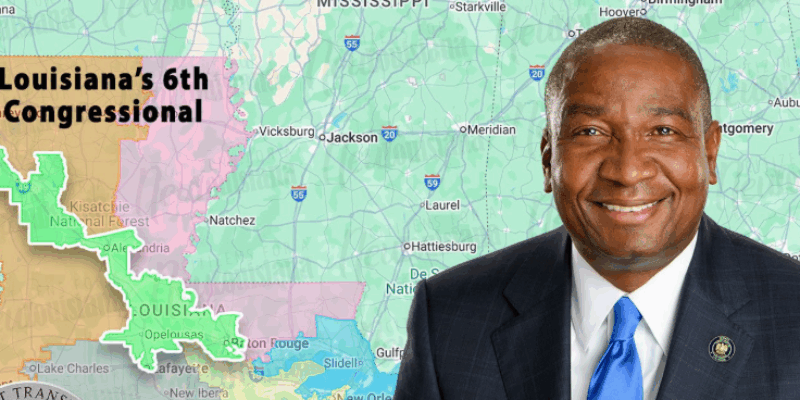

That same backward glance is playing out in Louisiana today, where the political and legal battles over U.S. House District 6 have less to do with the realities of modern elections and more to do with replaying the scripts of the 1960s. In the ongoing case before the U.S. Supreme Court, Louisiana’s legislature, under federal court pressure, redrew its congressional map to create a second majority-Black district — not because the current political conditions organically demanded it, but because the Voting Rights Act, as interpreted through decades-old precedents, was used as the lever to force it.

The Cleo District and the National Stakes

The result is a district configuration designed with race as the overriding factor, sidelining traditional redistricting principles like compactness, community cohesion, and logical geographic boundaries. The plaintiffs now argue, correctly, that this racial predominance crosses the line into unconstitutional gerrymandering. At the same time, the defendants claim it is a necessary remedy to comply with Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

For decades, the courts have wrestled with how to draw that line. In Thornburg v. Gingles (1986), the Supreme Court created a three-part “preconditions” test to determine when Section 2 requires a majority-minority district: the minority group must be large and compact enough to form a district, politically cohesive, and regularly defeated by bloc voting from the majority. This test, intended to address “voter dilution” (or perhaps delusion), has since been used as a blueprint for race-driven districting — sometimes in places where the original problem it sought to address no longer exists.

In the 1990s, cases like Shaw v. Reno and Miller v. Johnson added the “predominant factor” test, holding that when race is the primary driver of district boundaries, the plan must withstand strict scrutiny — meaning it must serve a compelling interest and be narrowly tailored. More recently, in Allen v. Milligan (2023), the Court reaffirmed Gingles but left the door open to expansive Section 2 remedies, setting the stage for Louisiana’s current bind. The evolution of these tests shows a judiciary torn between two imperatives: honoring the anti-discrimination mandate of the Voting Rights Act and enforcing the Equal Protection Clause’s prohibition on racial classifications. Ultimately, the Constitutional argument should prevail, and the Voting Rights Act, at least in part or in its application, should be deemed unconstitutional.

Peeling Back Federal Intervention

The conflict in Louisiana is a microcosm of a broader problem — the way federal intervention, brought on by the turmoil of the 1960s, has become an entrenched and self-perpetuating force in state election law. What began as a targeted effort to dismantle specific barriers to minority voting has morphed into a permanent mandate for Washington to second-guess the sovereign choices of the states. The more the courts stretch the Voting Rights Act beyond its original purpose, the further they drift from the enumerated powers the Constitution actually grants.

If the judiciary continues to treat Section 2 as a tool for engineering racially “balanced” outcomes rather than preventing disenfranchisement, it ceases to function as a protection of rights and instead becomes a political instrument. Louisiana’s case is not just about one oddly drawn district — it is about whether the federal government can compel states to abandon neutral redistricting principles in service of a racial quota system, decades after the conditions that brought on such measures have changed or disappeared entirely.

A Ruling That Could Reshape America

The stakes extend far beyond Louisiana’s borders. If the Court rules that race-driven districting under Section 2 violates the Equal Protection Clause, it could trigger challenges to congressional and legislative maps in multiple states where majority-minority districts were drawn primarily to satisfy the Gingles formula. Such a decision would likely lead to the dismantling or consolidation of several minority districts nationwide, replacing them with maps based on traditional criteria, including compactness, contiguity, and respect for political boundaries. For those committed to a constitutional order rooted in state sovereignty and equal treatment under the law, this would mark a long-overdue course correction; for others, it would be seen as a rollback of decades of political gains. Either way, Louisiana’s fight may well decide the shape of representation in America for a generation.

And this isn’t just theory. The political map is already shifting beneath our feet.

Only Louisiana Can Finish this Fight

Across the nation, states are already redrawing maps. Governors and legislatures in over two dozen states are quietly reshaping congressional districts in ways that could dramatically alter national power balances. But Louisiana offers something the other states can’t: a definitive legal ruling. One that could outlast election cycles and rewrite the rules for a generation. One that could restore constitutional clarity to redistricting, reaffirm state sovereignty, and rein in the racial engineering that has dominated map-drawing since the Gingles decision.

If Louisiana redraws its own map now, the case could be mooted — and with it, the opportunity to stop a dangerous trend that’s quietly replacing the principle of “one person, one vote” with “one race, one district.” By standing firm, Louisiana holds the line — not just for itself, but for every state still governed by the rule of law.

Whether you believe in the Voting Rights Act’s original intent or see it as a relic of a bygone era, one thing is clear. Louisiana has brought the entire country to a constitutional crossroads. What Louisiana does next will decide which direction our nation takes. As a small state, Louisiana is wagering just one congressional seat. But if the case succeeds, the conservative movement could gain twenty-five or more.

Advertisement

Advertisement