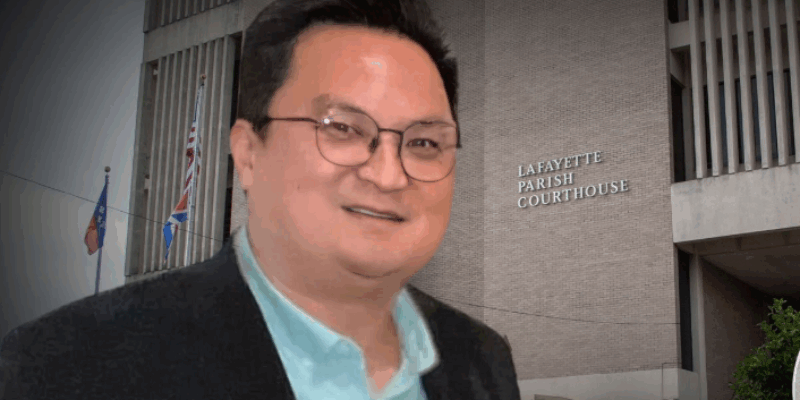

(Citizens for a New Louisiana) — Eddie Lau was arrested in March 2025 on charges of allegedly spreading knowingly false information during the Senate District 23 race. To some, the arrest came as a shock, but so many more were not surprised. But then … silence. What’s going on, who’s involved, and, most importantly, when will it ever get prosecuted?

We Told You So, Again!

Back in February, we were the first to discuss the ‘fake’ text messages which were being disseminated and other tactics deployed over the last few months. At that time many people had taken notice of the sheer number of messages being sent during the Senate 23 race which pitted then State Representative Brach Myers (R 7/10) against Broussard City Councilman Jesse Regan (R 6/10), in a special election to fill the seat vacated by Jean-Paul Coussan (R 7/10), some of which were blatantly originated from fake sources. We received calls from Conservatives and Konservatives alike inquiring about our articles. Some wanted us to “stay out of it”, while the large majority were genuinely concerned about the effect such widespread misinformation could have on the outcome of our elections.

Remember, misinformation was fresh on the minds of many. What had occurred during the draconian days of COVID was coming to light and it was horrifying. How could our own government get away with such pervasive lies and misinformation which ultimately ruined the lives and careers of many? And was this now spilling over into our local politics?

Opening Arguments

If the Eddie Lau trial were to begin today, we suspect open arguments by the prosecutor would go something like this:

Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, this case is about a lie — not a mistake, not a difference of opinion, but a deliberate, calculated falsehood told in the heat of a political campaign.

The defendant, Eddie Lau, served as the campaign manager for Candidate Jesse Regan in the 2025 race for Louisiana Senate District 23. As you will hear, Eddie Lau had a direct financial incentive for Candidate Jesse Regan to win. It is not uncommon for contracts between campaign managers and candidates to include a bonus tied to victory. But deliberately lying to the public in an attempt to sway the outcome of an election for financial gain is despicable and un-American. It isn’t that much different from the other types of criminal fraud we have on the books. Then all the monies flow from political leaders in the form of political patronage once they have secured the office sought. The financial gain is often concealed within the official business of the public body to give it the appearance of legitimacy. Lau would have been in a position to receive such benefits.

On February 1, 2025, a text message was circulated to voters across the area, stating that Brach Myers — the opponent of Jesse Regan — was in fact endorsed by the Lady Democrats of Acadiana.

Knowingly False Statements

That statement was false. It was not partially true, not misremembered — it was entirely made up. The Lady Democrats of Acadiana never endorsed candidate Myers. And the defendant knew it. Not only did he know it, but he also took deliberate steps to conceal his involvement in the fact that the message originated from the Regan camp. Jesse Regan himself made a public statement indicating that his campaign had nothing to do with the message. All lies!

How do we know the defendant knew? Because the campaign’s own internal documents — opposition research files, emails, and messages — show that they knowingly and intentionally conspired to send out false information. They knew the statements were false. However, they also knew that the accusation would be damaging in the final weeks leading up to the election.

You will also hear testimony from a defector of the Regan campaign. Someone who was involved in discussions about intentionally sending false information out to the voters, but said ‘NO. I will not be a part of this.’

What You Will Hear

The law in Louisiana is clear: you cannot, in the course of an election, knowingly make a false statement of material fact about a candidate with the intent to influence the outcome. This isn’t about silencing political debate or criminalizing opinion. It’s about protecting voters from calculated fraud in the most important decision they make — choosing their representatives.

- Testimony from the campaign defector, confirming that Lau and others with the Regan campaign knew the statements were false and intentionally chose to spread them to influence the outcome of the election.

- Internal campaign emails in which the defendant acknowledges the falsity of the statements but decides to move forward anyway.

- The defendant’s contract and other documents showing how the defendant expected to financially benefit from spreading false and fraudulent information.

- The actual text messages that were circulated to the public.

By the end of this case, you will see that this was not a slip of the tongue or a misunderstanding. It was a deliberate lie, told for personal and political gain, in direct violation of Louisiana’s election integrity laws. We will ask you to hold the defendant accountable — because in Louisiana, the truth still matters.

The Prosecution

Of course, for the Lau matter to even reach trial, it must overcome a few hurdles. First, the District Attorney, Don Landry, has to file charges against Lau. Landry has not filed a bill of information, nor has a formal grand jury indictment occurred, charging Lau with a crime.

There is also a question as to whether Lau can be subjected to prosecution by Landry, given the possible existence of a conflict of interest. Although Lau or his companies don’t appear to be present in the campaign finance reports of Landry, it is not necessarily the case that Lau didn’t work for Landry.

Lau is well-known in political circles and has worked with numerous local and state political officials. In some cases, his name appears on their reports, and in other instances, it doesn’t. Such is the case of Iberia Parish Tommy Romero. Lau openly advertised on his website that Romero was a client. However, in response to a public records request, Romero indicated his office had no documents responsive to our request. Likewise, Romero doesn’t list Lau or his companies in his campaign finance reports.

The Attorney General

If it is determined that District Attorney Don Landry has a conflict of interest in handling the prosecution of Lau, it would then be kicked to the Attorney General, Liz Murrill. The campaign finance reports of Murrill don’t indicate any payments to Lau or his companies either. But again, Lau is absent from the campaign reports of others for whom he has worked.

There is a likelihood that Lau was subcontracted by other campaign managers and consultants, thus allowing him to escape being reported on a candidate’s finance report. All it takes is one degree of separation. Therefore, we may never know all the campaigns Lau has worked on.

Let’s say, for the sake of mental exercise, that both Landry and Murrill have conflicts of interest that would prohibit them from prosecuting Lau. Then what? Under that scenario, the case would likely find itself in the hands of a rural District Attorney who has no dog in the hunt, but who also would be less inclined even to want to deal with it.

The Constitutional Argument

Last month, Lau, through his attorney, filed a Motion to Quash Search Warrant, Suppress Evidence, and Return Seized Items. Lau asserts that the warrant was based on a law that was ruled unconstitutional over 35 years ago. The debate over the limits of free speech has been ongoing since the country’s inception.

Under the Constitution, the right to free speech is protected by the First Amendment, which was ratified in 1791. That is what we have all been taught and have come to believe, but it just isn’t that straightforward. “Congress shall make no law… abridging the freedom of speech.” At the time of its enactment under our original Confederated Constitutional Republic, that amendment ONLY applied to the federal government. It was a negative right to prohibit Congress (the only branch with national law-making power) from enacting laws, but it did not apply to the states.

While many states had clauses in their state constitutions that secured the rights of individuals from encroachment by the state government, that was not the intent of the First Amendment. The founders also didn’t envision the system we have today, where the Executive can issue an order, which is then carried out as though it had the force of law. Or a Judiciary that can create new “rights” binding on both the Executive and the Legislature by Judicial edict. It was a simple construction that has been morphed and abused over the years. The First Amendment was intended to restrain the federal government from exercising any authority over freedom of speech, while allowing the states to do as they wished.

The Sedition Acts

Of course, it wouldn’t be long before the First Amendment would be tested. The Federalist party controlled all three branches of government. President John Adams was a Federalist; Federalists controlled the Congress, and Federalist-appointed judges dominated the federal judiciary. Out of this one-party domination of the federal apparatus came the Sedition Act which made it a criminal act to “write, print, utter or publish…. any false, scandalous and malicious writing… against the government of the United States… with the intent to defame the same government…. Or to bring [it]… into contempt or disrepute… or to excite against [it]… the hatred of the good people of the United States…”

Interestingly, exempt from the law was criticizing the Vice President. That was because Vice President Thomas Jefferson was not a Federalist, and an election year was soon approaching. What followed was the earliest example of “interposition” or “nullification” with the states of Virginia and Kentucky issuing resolutions proclaiming the act unconstitutional and putting their agent in check. While the arguments pointed out that Congress can’t prohibit speech from being made (“prior restraint”), it was also well known under the British theory of “freedom of speech” that the Crown could punish someone after they had spoken. James Madison pointed out that under the American system, the prohibition applied to speech both before and after the fact.

The Supreme Court would never rule on the constitutionality of the Sedition Act. Jefferson defeated Adams, winning the Presidency in 1800. The Sedition Acts were repealed, and Jefferson pardoned everyone who had been prosecuted under them. Their fine money was also returned to them from the treasury. Benjamin Franklin Bache, the grandson of Benjamin Franklin, was one such person arrested for criticizing President Adams.

War Time Acts

War time always serves to undermine our fundamental rights. The outbreak of the Civil War was no exception. During this time in American history, the Lincoln administration shut down newspapers, arrested editors, and suspended habeas corpus in some speech cases seen as aiding the Confederacy. Francis Key Howard, the grandson of Francis Scott Key, would find himself imprisoned at Fort McHenry for eighteen months during this time.

World War I would lead to the Espionage and Sedition Acts, which were swiftly implemented by the administration of President Woodrow Wilson in an effort to silence critics. The Espionage Act was quickly challenged by Charles Schenck, a person who was charged and prosecuted for voicing opposition to the military draft. The Supreme Court unanimously upheld the conviction of Schenck, with Justice Oliver Holmes remarking: “The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic.” Holmes specifically called out a “lie” as not being protected if it would cause panic. This gave rise to what is commonly known as the “clear and present danger” doctrine. Five decades later, in 1969, the Court would essentially reverse the Schenck ruling.

The Red Scare and World War II would give rise to other laws and regulations regarding free speech. The Office of Censorship (1941–1945) controlled the publication of sensitive information. The Smith Act criminalized advocating for violence against the U.S. government or belonging to groups that did so. Of course, violent overthrow of the U.S. government is no longer the strategy. It is now being accomplished from within, such as subversive attempts to sway the outcome of elections.

Today’s World

There have been many interpretations and cases decided in the arena of Free Speech since 1800. Very few people today argue that someone has an absolute right to free speech. Expression has become a part of protected speech. The use of money has become analogous to speech. But not all speech is protected from government regulation.

If someone lies about you and you are damaged, you can sue them for their speech, whether spoken or written. It is called defamation and libel. If someone utters words that are threatening to you or that cause panic, they may also be prosecuted for a crime. Threats, obscenity, incitement to imminent lawless action, fraud, perjury, and certain commercial misrepresentations are all examples of how speech has been restricted and criminalized.

The Supreme Court addressed a case involving a public official in 1964, New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, in which it ruled that speech about a public official or candidate is protected unless it is a false statement of fact.

Louisiana’s Political Speech Law

Our state legislature, in enacting Louisiana Revised Statute 18:1463, outlined the objective:

“The Legislature of Louisiana finds that the state has a compelling interest in taking every necessary step to assure that all elections are held in a fair and ethical manner and finds that an election cannot be held in a fair and ethical manner when any candidate or other person is allowed to print or distribute any material which falsely alleges that a candidate is supported by or affiliated with another candidate, group of candidates, or other person, or a political faction, or to publish statements that make scurrilous, false, or irresponsible adverse comments about a candidate or a proposition.”

Should a person who has a financial incentive to influence the outcome of an election be allowed to speak or publish a lie against or in favor of a candidate or proposition during the election cycle? That is what this all boils down to.

Advertisement

Advertisement