When it comes to Modernism, it is difficult to delineate between when the music started and when the dance floor ballooned into a buzz.

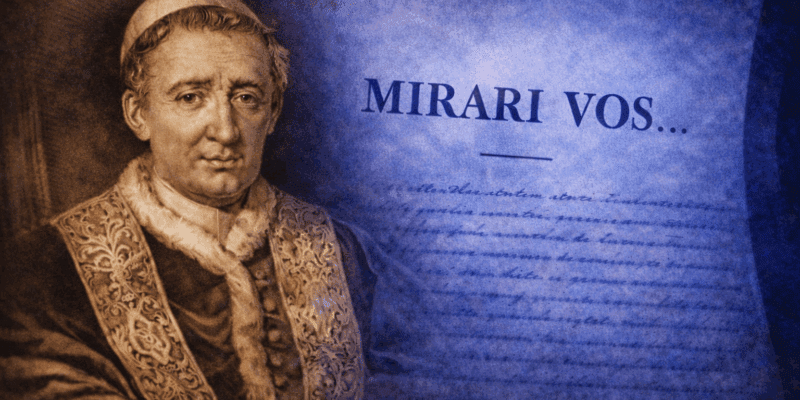

Regardless of where the true cause and effect lie, the storm of treason has most certainly buckled the dance floor. And we need look no further for the reasons why than the authoritative and perennial documents of the Church, in our case today once again, Mirari Vos by Pope Gregory XVI, who was one of a litany of Roman pontiffs starting around the time of the French Revolution warning with shepherd’s zeal what wicked things were brewing.

2. We were again delayed because of the insolent and factious men who endeavored to raise the standard of treason. Eventually, We had to use Our God-given authority to restrain the great obstinacy of these men with the rod.[2] Before We did, their unbridled rage seemed to grow from continued impunity and Our considerable indulgence. For these reasons Our duties have been heavy.

6. These and many other serious things, which at present would take too long to list, but which you know well, cause Our intense grief. It is not enough for Us to deplore these innumerable evils unless We strive to uproot them.

There indeed was cause for such grief.

When Mercy Hesitates

Pope Gregory is teaching, likely after trial and tragic error, that indulging in the treasonous designs of the enemy does not win that enemy over to the Church. This anticipates similar confessions in Pascendi by Pius X, who says that one step in the shepherding process was an attempt at kindness to the Modernists. Seemingly, as I study these encyclicals, authority hesitates not from cowardice, but from misjudged mercy. It is this exact hesitation, however, that has proven fatal as other authority figures have hijacked the hierarchy. To Pius X’s great sorrow as well, kindness did not work. No pope, apparently, could ever fully “uproot them.”

Kindness with demons does not dissuade them—it only teaches them how to move with you until you die off. If there is anything to learn from this, it is patience, and in the Christian sense, long-suffering.

This consistency across the encyclical landscape foregrounds a very important, if sinister, dance: delay in the uprooting leads to indulgence, which leads to the disintegration of Catholic morals—most pertinent for our purposes today—happening together, not sequentially.

This means that, despite God’s justice holding shepherds more accountable than the shepherded, ultimately a fallen soul is a fallen soul. Crisis does not begin with rebellion nor result from indulgence—they can arise together, feeding one another’s rhythm. All share blame for this catastrophic collapse in historical understanding and morals.

Still, Gregory (and Pius for that matter) does echo Scripture that says woe to those who lead young ones astray. The purpose of this piece is to show the dance, sure, but it is also worth noting first the separate wrath shepherds earn for their malice, not to kick them further down into the abyss, but to illustrate to unwary Catholics that, once upon a time, the words of teachers were “just a little different”:

6. We take refuge in your faith and call upon your concern for the salvation of the Catholic flock. Your singular prudence and diligent spirit give Us courage and console Us, afflicted as We are with so many trials. We must raise Our voice and attempt all things lest a wild boar from the woods should destroy the vineyard or wolves kill the flock. It is Our duty to lead the flock only to the food which is healthful. In these evil and dangerous times, the shepherds must never neglect their duty; they must never be so overcome by fear that they abandon the sheep. Let them never neglect the flock and become sluggish from idleness and apathy….

7. Indeed you will accomplish this perfectly if, as the duty of your office demands, you attend to yourselves and to doctrine and meditate on these words [of Pope St Celestine]: “the universal Church is affected by any and every novelty” and the admonition of Pope Agatho: “nothing of the things appointed ought to be diminished; nothing changed; nothing added; but they must be preserved both as regards expression and meaning.”

8. …It is the duty of individual bishops to cling to the See of Peter faithfully, to guard the faith piously and religiously, and to feed their flock. It behooves priests to be subject to the bishops, whom “they are to look upon as the parents of their souls,” as [St] Jerome admonishes. Nor may the priests ever forget that they are forbidden by ancient canons to undertake ministry and to assume the tasks of teaching and preaching “without the permission of their bishop to whom the people have been entrusted; an accounting for the souls of the people will be demanded from the bishop.”

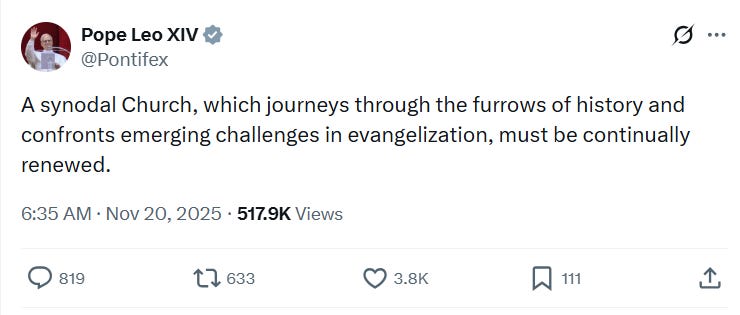

Is there any more exhibit needed than this Agatho and perennial Church teaching in paragraph 7, when juxtaposed with a tweet and familiar Modernist teaching like the following?

Or with a document like Fiducia Supplicans?

Such “renewal” and “novelty” lauded by Modernists and warned about by the likes of Pope Celestine feels necessary to the mob only when disorder and negligence have long taken over. In the absence of God’s commanded order, novelty provides a false stabilization to the chaos, just long enough for it to spread. In the name of liberty—remember Gregory is writing on the heels of the French Revolution—everyone gets an opinion, everyone can “speak his truth,” everyone can “do you.” Indeed, Gregory’s words traverse the centuries and speak directly to Leo’s tweet:

10. …Therefore, it is obviously absurd and injurious to propose a certain “restoration and regeneration” for her as though necessary for her safety and growth, as if she could be considered subject to defect or obscuration or other misfortune. Indeed these authors of novelties consider that a “foundation may be laid of a new human institution,” and what Cyprian detested may come to pass, that what was a divine thing “may become a human church.”

Human church. Human hands. The horizontal beam of the cross alone.

The distinction in teaching is clear, and is one reason I study and write on papal encyclicals. If only more Ordinary Form Catholics would have the courage to juxtapose past teachings with the present, they would see that there can be no continuity in them, as has been claimed by Modernists. The exhibit room proves—by the contradiction of the words themselves—that we are dealing with two completely different papal teachings.

What studying past popes’ instruction does as well is keep the notion and necessity of authority at the center of our journey back to Christ and his Church. My subtitle in yesterday’s article included “Watching the watchmen and the fractures inside Tradition has become the unenviable job of imperfect laymen.” This shouldn’t be the charge of laymen to fight this fight; I shouldn’t even be writing this article. But at this moment in history, seemingly it is the charge, else we and our loved ones go merrily and murderously down the way of the Modernist. But what we can do, in my humble and perhaps erroneous opinion, is hold true to the perennial teachings of popes and councils as the anchor.

Liberty Without Order

When ignorance rules the day and such older teachings are summarily rejected, the Church faithful feel pressured to change steps, to “keep up.” At some point, the faithful did not merely suffer from the shepherds’ negligence but learned to move with it, to adapt to both the hesitations and kindnesses of the good shepherds and the novelties of the bad. As authority of all varieties blurred, so softened the conscience, the disciplines, the armor of Christ’s Church. It was and is a most insidious desensitization of the soul, and the bystander effect goes from textbook to real life—

“Who am I to judge?”

What Gregory identifies here is not a single doctrinal error introduced at a discrete moment, but a shared movement between negligence and novelty, where mercy untethered from truth and liberty unleashed from order begin to step together, each excusing the other:

14. This shameful font of indifferentism gives rise to that absurd and erroneous proposition which claims that liberty of conscience must be maintained for everyone. It spreads ruin in sacred and civil affairs, though some repeat over and over again with the greatest impudence that some advantage accrues to religion from it. “But the death of the soul is worse than freedom of error,” as Augustine was wont to say. When all restraints are removed by which men are kept on the narrow path of truth, their nature, which is already inclined to evil, propels them to ruin. Then truly “the bottomless pit” (Apoc 9:3) is open from which John saw smoke ascending which obscured the sun, and out of which locusts flew forth to devastate the earth. Thence comes transformation of minds, corruption of youths, contempt of sacred things and holy laws — in other words, a pestilence more deadly to the state than any other. Experience shows, even from earliest times, that cities renowned for wealth, dominion, and glory perished as a result of this single evil, namely immoderate freedom of opinion, license of free speech, and desire for novelty.

Will the United States of America be in that last number?

Liberty of conscience, then, is not merely tolerated error; it is the atmosphere created when truth and authority retreat at the same time.

For American Catholics, regarding such accepted “virtues” as liberty, how do these teachings stack up with what is coming out of Rome and from pulpits around the country today? Where do we think the moral decay of society comes from?

Is our answer really “the woke left,” as though our cooperation in the reality God commands wouldn’t be enough to vanquish such a ridiculously puny “cause”?

The Two-Step

What makes Gregory’s warnings so unsettling is that he never allows the crisis to remain safely “up there,” confined to bishops, popes, or distant structures. Even as he speaks forcefully about authority, he assumes something modern Catholics resist admitting: that the flock learns the steps of the dance whether or not the shepherd intends to teach them.

Authority falters, yes—but the laity, often formed by omission rather than commission, not to mention friendships with people of conflicting creeds, begin to supply their own theology, their own moral language, their own sense of what is “reasonable,” “religious,” even “too rigid.” The dance floor is ever-expanding not out of conscious rebellion, but because accommodation feels safer than the fight.

It was why people who loved Christ shouted amidst the mob for his crucifixion. It’s why Peter denied Jesus three times while warming himself by the fire.

It’s just… easier.

For the enemy, no coup is required, no battle is needed, when desensitization does the work. Gregory’s grief, then, is not reserved for these enemies alone. It extends to a people who, through no single decisive act, have grown comfortable—indeed normal—in the movement without guardrails. The faithful continue to show up, continue to “participate,” continue to speak the language of belief—yet increasingly do so without friction, without sacrifice, without resistance, without fidelity to being truly and unapologetically Catholic.

The Church Militant thus has been erased behind sentiment, obedience to vibes, and an ever-eroding sense of what Catholicism means. One need only hear someone say “I don’t believe in religion all I need is Jesus” to see how far the deception has gone, as though “needing Jesus” can be severed from his commands and the Body he established.

The faithful, then, remain on the floor, convinced they are still dancing with the Church, even as the music has changed entirely. It is similar to what the writers of the Alta Vendita laid out when they set their sights on getting one of their own to eventually rise to the Chair of Peter, all the while thinking he was carrying the flag of Catholicism and the apostolic keys. Inside such comfort, such surety despite the moral chaos all around, the bystander effect sets in. Each understands something could be wrong, but ultimately chooses to wait for someone else to object (preferably someone important on TV!), and if no one does, it must be that nothing is wrong.

And every single Jeremias and Stephen out there must be stoned.

The Final Step

Pope Gregory XVI does not leave us merely diagnosing a dance, nor should we. If negligence and novelty move together, then for the Church Militant—the Remnant—resistance must also be lived, not merely argued in the pages of a digital space.

The first act of resistance is repentance. Not performative repentance, not rhetorical repentance, but actual examination of conscience, confession, and submission of the will to God’s order rather than the spirit of the age. A soul that kneels regularly does not remain comfortably numb for long.

The second is the sacramental life itself. Frequent confession restores moral clarity. The Holy Eucharist, received worthily, re-anchors the soul in objective reality when everything else insists that reality is negotiable. Grace recalibrates what endless commentary cannot. Yes, amid the liturgical wars perhaps it is unclear where the true sacraments lie. Hopefully, they exist in all forms we’ve come to believe in, but the important thing is that we act this duty out according to our state on the path. I addressed different states on the path here in my last article.

And finally, as a direct bloodline to understanding our state on the path, there is the Rosary.

This is not a Taylor Marshall-type pitch to be “on the team.” This isn’t something so trivial as to slip into sports metaphor or something to just “get done” before bed time, even though admittedly that sometimes has to be the case. As a rule and not the exception, it needs to be said daily, not sporadically, and three or six or nine times in a single day every now and then if we can. Ask Padre Pio to help you.

The Rosary does something modern Catholics underestimate: it slows the dance. It retrains the imagination. It places the soul back into a rhythm not of novelty, but of repetition ordered toward those fifteen divine mysteries of Our Lord. Our Lady does not shout over the music. She teaches us in the whisper of Elias, when to stop dancing, when to stand still, when to exit the dance floor altogether.

This is not quietism. It is not retreat or isolation from the world. It is re-orientation within it.

It is Our Lord removing Himself at times from the crowd to pray alone and us doing what He does.

The dance floor will remain crowded till our dying day. The music will keep feeding the bones, enticing us to the dance. But a Catholic who prays, confesses, and submits himself to sacramental reality and to Christ’s Mother no longer needs to keep up.

He can step aside.

He can kneel.

And he can hear the voice of his Shepherd speaking long before the noise began.

Advertisement

Advertisement