THE PILLARS OF THE REPUBLIC

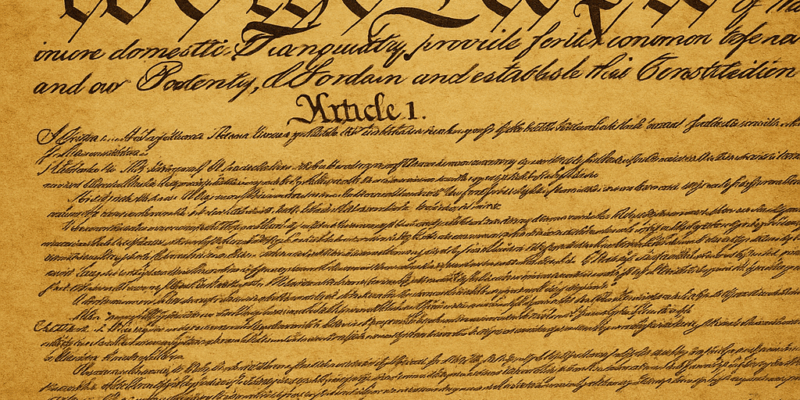

In 1789, beneath a canopy of uncertainty and hope, George Washington stood on the balcony of Federal Hall in New York City and took the oath of office as the first President of the United States. The Constitution had only recently been ratified, having been adopted by the Constitutional Convention on September 17, 1787, and ratified by the States thereafter. The ink was barely dry. The nation was a fragile experiment in republican government unlike any the world had seen. As Washington placed his hand on the Bible borrowed from the local Masonic Lodge and swore to “preserve, protect and defend” this new charter, he must have felt the weight of history pressing on his shoulders.

There was no precedent to follow, no executive tradition to inherit. He only had the trust of a fledgling people and the framework of a document that sought to bind liberty with law. Washington, ever conscious of duty and legacy, surely felt anxiety about the enormity of the task.

As he spoke to those assembled, in what would become America’s first Presidential Inaugural Address, Washington articulated several ideas that still resound today. First, Washington believed that God had been instrumental in the Nation’s new liberties. He noted that “[e]very step by which [the American people] have advanced to the character of an independent nation seems to have been distinguished by some token of providential agency.”

He also believed that morality and religion were instrumental to the success of the new nation and its new Constitution. Again, he noted, “we ought to be no less persuaded that the propitious smiles of Heaven can never be expected on a nation that disregards the eternal rules of order and right which Heaven itself has ordained.”

In his Farewell Address, Washington echoed these sentiments and made his conviction plain: “Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports.” These were not ornamental virtues but were the pillars on which the republic and its Constitution stood. Without them, even the most artful constitution would collapse under the weight of self-interest and faction.

Washington was not alone in this belief. John Adams wrote that “our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.” Benjamin Franklin, though less doctrinal, warned that liberty without virtue would become license. Even Thomas Jefferson, often cast as the secular counterweight, acknowledged that “the moral sense… is as much a part of man as his leg or arm.”

The Founders understood that the Constitution was not self-executing. It required a citizenry capable of self-restraint, guided by conscience, and animated by shared values. Religion and morality were not merely private matters but were public necessities. They formed the unwritten code that made written law meaningful.

As we celebrate Constitution Day on September 17, some 238 years after its adoption by the Constitutional Convention, let us remember that the enduring strength of our Constitution depends as much on the character of its people as on the words of its text. Let us recommit ourselves to lives of integrity, compassion, and faith, nurturing both our own moral compass and the shared values that bind us as a nation. By striving to live with virtue and morality, we not only honor the vision of the Founders but also secure the blessings of liberty for generations yet to come.

Advertisement

Advertisement