It has been 10 years since Oklahoma joined the ranks of Right-to-Work states, becoming Number 22.

It has been 10 years since Oklahoma joined the ranks of Right-to-Work states, becoming Number 22.

Now Indiana has become Number 23.

The legislation recently enacted in the Hoosier State is potentially a game-changer in the workplace. The upper Midwest was a bastion of manufacturing and union dominance for decades. In post-World War II America, that region ruled when it came to manufacturing steel, automobiles, and durable goods of all types. The industrial might of the region was tempered only by the clout of the industrial unions that used their muscle to secure contracts that drastically and systematically increased wages and benefits and imposed burdensome work rules on employers. The result was diminished productivity and higher manufacturing costs.

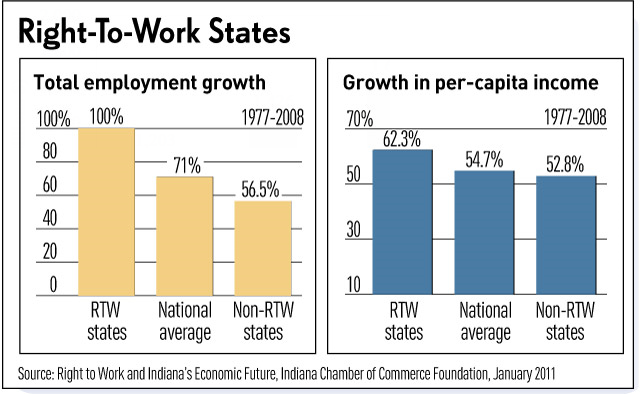

As productivity declined, manufacturers looked to relocate in areas less dominated by trade unions. Companies shifted their operations to Right-to-Work states in the Sunbelt and to offshore locations where labor costs were not prohibitive and union work rules were not an impediment to increased productivity. Foreign automobile manufacturers, for example, have located their American production facilities exclusively in Right-to-Work states.

Indiana led the U.S. in manufacturing activity for years. As the top manufacturing state, it also led the nation in the number of lost manufacturing jobs over the last few decades. Indiana finally decided that it had had enough.

The impact of Indiana’s passage of Right-to-Work will likely be felt in a pronounced and immediate fashion in the upper Midwest. Michigan, Wisconsin, Illinois, Minnesota, Ohio, and Pennsylvania will be entering a different economic climate as Indiana successfully markets its status as the newest Right-to-Work state in the nation. A state in their own backyard will now have a strong competitive edge when it comes to recruiting new industries or expanding existing ones. Indiana’s neighbors are going to have to strongly consider enacting their own Right-to-Work laws. Some already are.

There will always be unions in Indiana and all of the other Right-to-Work states. The difference is, the unions in the Right-to-Work states have to be more responsive to the needs of their members and have to provide real value to earn their dues dollars. In the Right-to-Work states, the employees are free to choose whether or not they want to pay dues to a union.

The drastic reduction in the percentage of the U.S. workforce in private sector unions is not the direct result of the growth in the number of Right-to-Work states. It is more a factor of poor marketing tactics by the unions. Union leaders and organizers are still stuck in the rut of thinking that they can use intimidation and political dominance to grow their ranks. Those days are rapidly coming to a close. If the unions want to succeed, they need to sell themselves to employers as a positive force in the work place, not a negative drag on productivity.

The unions have a very valuable commodity to sell: skilled labor. Their downfall has come from the fact that they don’t think they need to sell themselves to employers. They do. Union leaders who could approach employers in a positive fashion regarding productivity partnerships could meet with greater success in signing collective bargaining agreements. But they would have to throw out the ridiculous work rules that are crammed into current union agreements and convince employers that they want to increase productivity and profitability so they can share in it. That train hasn’t left the station yet. Until it does, more states will join the Right-to-Work ranks and those left out will continue to see their manufacturing sectors shrink and more jobs move to Right-to-Work states.

Advertisement

Advertisement