…though a 79 percent increase in property taxes for the working poor to fund an unaccountable, antiquated, uneconomic and unattractive bus system without any real plan for reforming its operations is an atrocity in itself.

…though a 79 percent increase in property taxes for the working poor to fund an unaccountable, antiquated, uneconomic and unattractive bus system without any real plan for reforming its operations is an atrocity in itself.

The Capital Area Transit System can’t survive on $12 million a year for 3,900 riders, running a $2.1 million deficit, and it now wants $18 million extra in local taxes that it says will enable it to become viable. Anyone who actually believes this is a good idea has lost his or her mind.

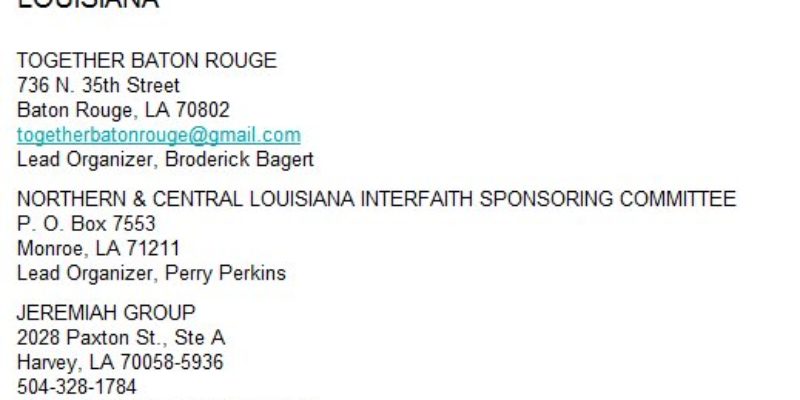

By the way, did you know that this Together Baton Rouge outfit which is pushing the bus tax is a Saul Alinsky front?

Well, now you do. Together Baton Rouge is an affiliate of the Industrial Areas Foundation, and the community organizer who runs Together Baton Rouge is an Industrial Areas Foundation operative.

What’s the Industrial Areas Foundation?

Established in 1940 by Saul Alinsky, the Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF) is a Chicago-based community-organizing network consisting of 59 affiliate groups located in 21 U.S. states as well as Canada, the United Kingdom, and Germany.

IAF’s mission is to “build organizations whose primary purpose is power — the ability to act — and whose chief product is social change.” Toward that end, an IAF training institute — which Saul Alinsky himself launched in 1969 as a “school for professional radicals” — trains community organizers in the tactics of revolutionary social change that its founder outlined. The institute has been headed by ex-seminarian Edward Chambers ever since Alinsky’s death in 1972. Its leadership-training programs consist of intensive 10-day sessions that are held two to three times each year. IAF also offers a 90-day internship program for aspiring organizers.

IAF is not a grassroots network; its local affiliates are created as the result of careful planning by its national leadership. According to the Rev. Johnny Youngblood, a former leader of the New York IAF local known as East Brooklyn Churches: “We are not a grassroots organization. Grass roots are shallow roots. Grass roots are fragile roots. Our roots are deep roots.” (emphasis ours)

IAF describes itself as “non-ideological and strictly non-partisan, but proudly, publicly, and persistently political.” As onetime IAF organizer Arnold Graf has stated:

“In places like San Antonio and Baltimore, we are as close to being a political party as anybody is. We go around organizing people, getting them to agree on an agenda, registering them to vote, interviewing candidates on whether they support our agenda. We’re not a political party, but that’s what political parties do.”

Similarly, Arizona’s IAF local — known as the Pima County Interfaith Council — is officially a Political Action Committee whose mission is “the collection and exercise of political power and influence.”

And we know that Together Baton Rouge is an IAF group because, well, the IAF’s own website says they are.

We also know it because Together Baton Rouge’s website gives away the store. Go to the “About” page and they’ll come right out and say it.

Together Baton Rouge is part of the Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF), the nation’s oldest and largest broad-based organizing network. There are more than 65 IAF organizations around the country, including projects in New Orleans, Monroe, Shreveport-Bossier, Alexandria and the Louisiana Delta.

Also, on the “Track Record” page on that site you’ll find this…

IAF organizations throughout the country have established a powerful track record for citizen-driven community change.

Below are a few key accomplishments of other IAF projects, that demonstrate the power and potential of institutions working together.

Following that are a host of accomplishments of IAF, each of which involve the procurement of redistributive government dollars to aid poor people on things like public transit, public education, public housing, public works and “living wage” regimes.

All of which might seem philanthropic, except for the fact that it isn’t the IAF’s money being spent – it’s government money. These people are outstanding at mining your wallet for unaccountable cash to fund their programs, and in doing so they serve as a conduit for Democrat politicians to buy votes in poor communities.

And that brings us back to Mr. Bagert, who is the head honcho community organizer for Together Baton Rouge.

Bagert, by the by, isn’t a Baton Rouge guy. In fact, he just got here a short time ago. Bagert is a New Orleans native, a 1994 graduate of Isidore Newman High School [edit: Jesuit High School] and a professional rabble-rouser who’s been celebrated in leftist New Orleans circles since he – as a 25-year old right out of the London School of Economics – stirred up the public-assistance community over the 2002 plan to clean up the St. Thomas Housing Projects in the Big Easy by replacing them with a mixed-use development including a Wal-Mart. Bagert loudly fought that project, which has been a major success in revitalizing an area formerly nicknamed “Little Vietnam” owing to the nightly violence emanating from St. Thomas into the Lower Garden District, and in doing so catapulted himself into the IAF’s pantheon of superstars, the most famous of whom is our current president.

But IAF didn’t want him to work in New Orleans, because his political connections in that city – Bagert’s father Brod, Sr. was a New Orleans City Councilman and public service commissioner before retiring from public life to pursue a career in poetry and his uncle Ben was a Democrat-turned-Republican state senator and unsuccessful candidate for the U.S. Senate (1990) and Attorney General (1991) – didn’t fit the organization’s model. IAF wants its organizers to be thrown into the deep end of the pool and make their own alliances and contacts – because in doing so their people can stay radical and not be encumbered by connections to the political mainstream. As such, he landed in Houston. And when Hurricane Katrina displaced over 100,000 New Orleanians with zero marketable skills or work histories to that city, Bagert happily appointed himself their champion. That advocacy, which ultimately involved a $75 million addition to the Road Home program designed to give former renters the ability to get “soft mortgages” and thus buy homes, turned out to be Bagert’s ticket back to New Orleans in 2006.

Bagert’s employer on his return home was an IAF organization called the Jeremiah Group, which has earned a reputation for left-wing radicalism emanating out of the city’s churches. And in his capacity as an organizer for that outfit Bagert could be counted on to show up at virtually every protest meeting about redevelopment of New Orleans along market principles; one could question his ability to get things done, as the Road Home addition wasn’t actually implemented in any significant posture until last year.

And from the Jeremiah Group Bagert made his way to Baton Rouge in 2010 as IAF founded Together Baton Rouge. After a couple of relatively insignificant initiatives – finding a receiver for an abandoned North Baton Rouge cemetery, fixing a bridge in the Glen Oaks neighborhood – Together Baton Rouge is making its first major splash with its bus-tax advocacy.

And in typical IAF fashion, Together Baton Rouge has penetrated many of the city’s churches to find volunteers and ground troops for the initiative. Interestingly, though, it’s not just the black churches the group has put hooks into. A list of churches and other organizations it claims to have recruited includes…

- AARP Louisiana

- Allen Chapel AME Church

- Baker Presbyterian Church

- Community Against Drugs & Violence

- Community Bible Baptist Church

- Donaldson Chapel Baptist Church

- Ebenezer Baptist Church

- First United Methodist Church

- Glen Oaks Baptist Church

- James A. Taylor Lodge #78, AF & AM

- Mid City Community Fellowship

- Mt. Carmel Baptist Church

- Mt. Pilgrim Baptist Church (35th Street)

- Mt. Pilgrim Baptist Church (Scenic Highway)

- Mt. Zion First Baptist Church

- National Association of Social Workers

- New Beginnings Baptist Church

- North Forest Heights Neighborhood

- Progressive Baptist Church

- Scotlandvile CDC

- SEIU

- Shady Grove Baptist Church

- Shiloh Baptist Church

- Southern University (School of Architecture & Center for Social Research)

- St. Alban’s Episcopal Chapel

- St. George Catholic Church

- St. James Episcopal Church

- St. Jean Vianney Catholic Church

- St. Luke’s Episcopal Church

- St. Mark United Methodist Church

- St. Mary Baptist Church

- St. Michael Episcopal Church

- St. Paul the Apostle Church

- Star Hill Baptist Church

- Unitarian Church of Baton Rouge

- University Presbyterian Church

- Wesley United Methodist Church

Many of those churches are of anything but the typical left-wing “social justice” model one might expect, but Together Baton Rouge sold their clergy on the concept of bringing black churches and white churches together for the common good of the community. This, as it happens, is an identical model to what the Jeremiah Group was doing in New Orleans. But in both places the effects have been devastating to the congregation of many of the churches involved once the true agenda of the group finally became clear.

“This affiliation with Together Baton Rouge has been a nightmare for us,” said one parishioner of a prominent local church we talked to, who asked that we not name him or his church because of the divisiveness of the issue. “Our vestry had no idea what we were getting into, and once we were hooked it became a major source of contention between members of our church, and particularly between many of our members and our pastor. How we get beyond this, I don’t know, but we’ve never had political divisions inside of our congregation before and we’ve definitely got one now.”

Which makes the Together Baton Rouge moniker a truly ironic one.

Should this tax pass, however, Baton Rouge will see a new power broker emerge, one which has national backing from a Hard Left Alinskyite organization, with a template and an agenda to follow – and that agenda will be redistributive. What’s more, the precedent of using municipal property taxes to fund “social justice” initiatives – and the bus tax is precisely that, as CATS could be made whole by a reallocation of East Baton Rouge Parish’s ample general fund to support it – will only lead to more of the same until the real estate market in town is weighed down by the tax cost of such programs.

Together Baton Rouge has continuously repeated its mantra that “you can’t have a great city without a great transportation system.” But Baton Rouge, as nice a place as it is, has never been and is not now a great city. It’s a mid-sized, suburban Southern city with a healthy industrial base, a state flagship university and a state capitol in it. There is nothing wrong with that status – what’s wrong with Baton Rouge is the city has horrendous public schools, bad traffic and a completely insufficient commitment to fighting crime, not to mention a sales tax rate higher than that of San Francisco. Nothing Together Baton Rouge advocates will alleviate those problems; soaking the rich and the middle class in order to subsidize entitlements for the poor will only hollow out the city as its tax base decamps for friendly bedroom communities, making the educational system worse, the resources available to fight crime more scarce and the traffic situation area-wide even more desperate; middle-class people don’t ride the bus whether they live in Southdowns or Sorrento.

If Baton Rouge is to ever be a great city, it will be as a result of great fiscal management, great advances in education and crimefighting, great economic competitiveness, great technological innovation and great fortunes being made. And should those things materialize, at some point there may be the opportunity and viability of a mass transit system on a greater scale than the one Baton Rouge has now. But if low ridership means a $2 million current annual deficit for the bus system, why should anyone believe that its business model will improve when it adds scads of employees and dozens of buses no one rides?

Together Baton Rouge hasn’t answered that question, because they’re not about economics. They’re about power. This bus tax is about giving that group credibility and stroke, and acclimating the working-, middle- and professional-class taxpayers in the state’s capitol city to funding nice-sounding ideas which ultimately constitute a political siphon from their pocketbooks and electoral heft.

The tax must be beaten, and decisively. If you’re able, vote No on Saturday.

Advertisement

Advertisement