Our readers may have heard about the revision to the state’s Coastal Master Plan, just out, which has gotten a good deal of publicity in the local papers. You can read the plan itself, without the attendant spin the Advocate and Times-Picayune have put on it (the latter hasn’t been too awful; the former, by the environmentalist kook and globa warming enthusiast Bob Marshall, is unreadable) by clicking here.

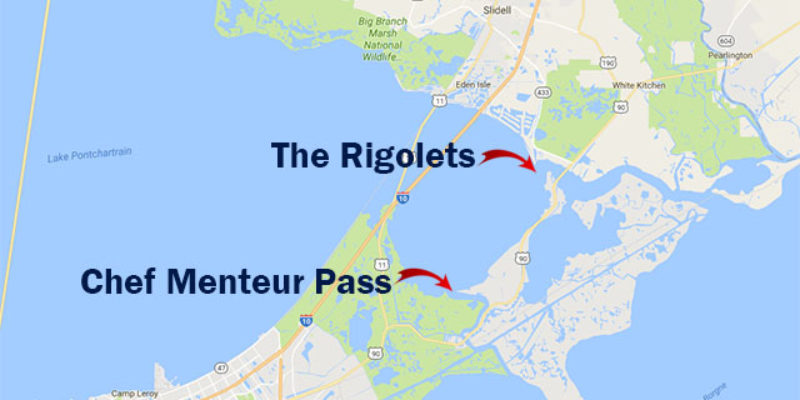

Perhaps the biggest-ticket item in the new plan is a $2.4 billion proposal for storm surge gates to be installed at the Rigolets and Chef Menteur Passes, which are two narrow waterways connecting Lake Pontchartrain with Lake Borgne, and by extension the Gulf of Mexico. The map in the image above should help with the geography for those who aren’t familiar; to the southwest of that map is New Orleans, and Slidell is visible in the top part of the map.

The reason those gates could be useful is that if you have a hurricane in the Gulf which packs a significant storm surge, shutting those gates could keep that surge from getting into the lake and flooding everything along the lakeshore. Lake Pontchartrain is an awfully big lake, and what’s more it also connects with Lake Maurepas to the west which is no fishpond, either. A very large chunk of land in Southeast Louisiana can be affected by those two lakes becoming over-full with water.

So the plan would be that levees get built or reinforced all along the coastline surrounding the connection between Lake Pontchartrain and Lake Borgne, and then storm gates are built so that the storm surge can’t get in. Where it goes then becomes a question; the folks on the Mississippi Gulf Coast probably aren’t all that enthusiastic about the idea of getting extra storm surge if it’s not allowed into Lake Pontchartrain, and if that storm surge were to back up into the Pearl River basin, you could well have floodwaters inundating from the north and east the same communities you’re hoping to protect from threats to the south.

But considering the vulnerability of the St. Tammany Parish communities from lake-borne storm surge, and the further vulnerabilities of Orleans and Jefferson Parishes on the south shore of the lake, and the vulnerabilities of the River Parishes to the west, which have taken flooding on numerous occasions thanks to water from Lake Pontchartrain, this might be a good idea. The Master Plan says the storm gates would eliminate some $1.2 billion per year in potential flood damage. Some $620 million of that number would come in St. Tammany Parish, with $292 million saved in New Orleans and Jefferson Parish. In the River Parishes the estimate is another $321 million in savings.

That’s assuming a couple of things, though.

First, as mentioned above – do you just displace the storm surge to someplace where it ends up flooding the same places anyway? Or does somebody else get flooded to pay for what the Rigolets and Chef Pass projects have saved? That’s debatable, and it will obviously vary based on what Mother Nature would throw at us.

But the second question is this – we saw in the August 2016 floods in south Louisiana that some of the areas on the south shore of Lake Pontchartrain can be flooded from rainwater coming out of the Amite River basin and into Lake Maurepas. That’s one reason part of the flood recovery appropriation the congressional delegation is fighting for includes some $800 million for levees in the northern part of St. John, St. James and St. Charles Parishes and in the eastern part of Ascension Parish. This matters, because a hurricane which brings enough storm surge that the storm gates at the Rigolets and Chef Pass would have to be closed might very well carry with it enough rain to flood the southeastern part of the state once it makes landfall. And at that point you want those gates open, not closed, because you’re trying to drain that water out to the Gulf. Does that storm surge the hurricane brought with it recede fast enough to just open the gates? We’re not hydrologists, but we are curious about that question.

Could be you’ve spent $2.4 billion on a project which might end up doing either negligible good or maybe even more harm than good.

The Times-Picayune says build the thing. We lean toward agreeing. But at one time it seemed like a hell of a good idea to levee the Mississippi all the way to its mouth so the river wouldn’t flood the land along its banks every year, and we now know that was the dumbest and most destructive thing the Army Corps of Engineers has ever done.

The one good thing about the storm gates is they can always just be left open if there’s a question about it being a bad idea to close them.

A parting shot – here are a couple of videos of what structures like this look like in Holland, where they damn sure know something about flood protection…

Advertisement

Advertisement