In two years’ time will occur perhaps the most lasting single consequence of Louisiana’s 2019 state elections, reapportionment.

By the end of 2021, the state must have districts drawn representing Congress, both chambers of the Legislature, the Supreme Court and courts of appeals, the Board of Elementary and Secondary Education, and the Public Service Commission, using the 2020 census data released at the end of that year. In all likelihood, this will occur by special session sometime in 2021.

Redrawing districts happens through the regular legislative process: a bill which must reach majority votes in each legislative chamber and gain gubernatorial assent defines these boundaries for each kind of government institution. If vetoed, two-thirds majorities override.

Only one institution might create any controversy. Legislative boundaries won’t change much, not only because Louisiana isn’t gaining much population but also because those districts will be drawn by legislators who will have gotten themselves elected under their current boundaries, with a relatively high proportion of newcomers in 2020 especially sensitive to this.

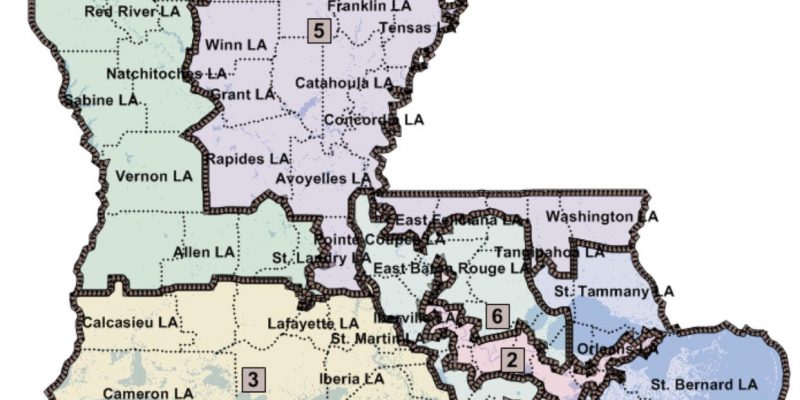

Little contention typically surrounds judicial boundaries and PSC and BESE boundaries are sufficiently large that marginal changes don’t affect the fate of any incumbent and the parties they represent. The six U.S. House of Representatives seats, however, may stir controversy.

Only one of these districts is majority-minority in a state where about twice that percentage of the population is non-white. However, residential patterns across the state make it difficult to draw constitutionally two majority-minority districts. So, in 2011 during the last round of reapportionment, Democrats tried to foist a plan that created a more substantial minority presence in the district with the next highest black representation, at 42 percent rather than the 38 percent eventually approved.

Republicans held the best hand because they had just acquired slim majorities in both legislative chambers and maintained the governor’s office. But in 2021, Democrat Gov. John Bel Edwards will wield veto power, and could try to use threat of its use to leverage a House district with a higher black population proportion to increase the chance of a Democrat winning that seat.

Advertisement

A GOP supermajority in the state Senate could override. But with Republicans two seats short of a House supermajority, it seems unlikely that any House Democrat would defect, and the two independents lean to the Democrats, so the House most likely would uphold a veto of a plan.

However, Republicans do have an ace in the hole. In the event that the state’s majoritarian branches can’t pass a plan by year’s end, the Supreme Court steps in. With its present and probable future composition of five Republicans, one Democrat, and a no-party justice, the Court likely would draw boundaries for 2022 elections closer to Republican than Democrat sympathies.

Legislative Republicans must account for this and send to Edwards only plans to their liking. For his part, Edwards probably will try a sitzkrieg by calling the special session early and if he backs a plan more advantageous to Democrats but must cast veto after veto of Republican plans, he would try to call more special sessions throughout the year to wear down the GOP. As long as that party’s members remain firm and have fortitude, they will back Edwards into a corner where he will have to accept their wishes.

Still, it may all make for great theater if not extra taxpayer expense, none of which can happen without Edwards having eked out a victory.

Advertisement

Advertisement