At least 17 states have authorized and or made withdrawals from their rainy day funds this year in order to fill budget holes, according to a new analysis by The Pew Charitable Trusts. Some withdrawals were small, others were more than half of what was set aside.

In fiscal 2020, at least 36 states had planned to make additional rainy day fund deposits but were constrained by fiscal and economic difficulties resulting from their respective state COVID-19 shutdowns, which resulted in increased unemployment and decreased revenue.

“Before the longest economic recovery in U.S. history came to an abrupt end, at least 33 states had saved enough to cover a greater share of government operating costs than in fiscal 2007, the last full budget year before the Great Recession,” the report states.

States had entered the 2020 budget year with a record $118.8 billion in total balances, including $75.2 billion in rainy day funds, Pew found.

Rainy day funds – also called budget stabilization funds – had grown for the ninth consecutive year, reaching a record 50-state total of $75.2 billion in fiscal 2019. Based on rainy day funds alone, states could run government operations for a median of 26.8 days, or an equivalent of 7.3 percent of their annual spending, a record high. Prior to the Great Recession, they could operate for about 17.3 days, or the equivalent of 4.7 percent of their spending.

“Overall, rainy day funds constitute the largest portion of states’ total balances, which comprise states’ intentional savings as well as dollars left over in what functions as a state’s main checking account – the general fund,” the report states. “Rainy day funds accounted for 63 cents of every dollar in total balances at the end of fiscal 2019, compared with 45 cents just before the recession.”

States use reserves to manage budgetary uncertainty, including revenue forecasting errors, budget gaps during economic downturns, and other unforeseen emergencies, such as natural disasters, the authors of the report explain. Having reserves can lessen the need for severe spending cuts or tax increases when states need to balance their budgets.

The fiscal fallout from the coronavirus shutdowns is projected to cost states at least $125 billion, according to an analysis by the Cleveland Federal Reserve. The Tax Policy Center projects states will lose up to $200 billion in revenue through fiscal 2021.

States have responded differently to coronavirus-era economic hardships. Ohio legislators have sought to preserve their state’s rainy day funds until they can better assess the long-term budgetary effects of the state’s shutdown.

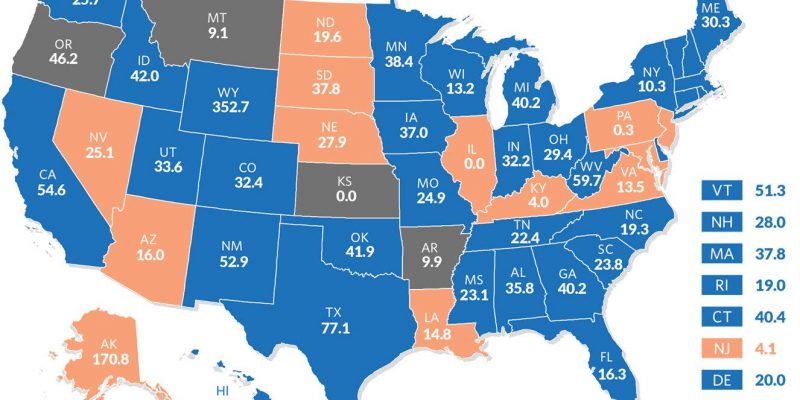

Unlike Ohio, Nevada and New Jersey have already completely drained their rainy day funds. Alaska, Rhode Island and California have withdrawn nearly half of their dedicated savings, whereas New Mexico’s planned withdrawal will reduce its rainy day fund by roughly 60 percent. Illinois didn’t have a rainy day fund to begin with.

Overall, at least 10 states have already used their rainy day funds to close budget gaps in fiscal 2020, according to the analysis: Alaska, Delaware, Maryland, Michigan, Mississippi, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Rhode Island.

“The withdrawals in Nevada and New Jersey marked a sharp reversal in two states that had made recent progress in replenishing their rainy day funds after emptying them during the previous downturn,” the authors of the report note. “In fiscal 2019, New Jersey made its first deposit in a decade, and Nevada surpassed its pre-Great Recession savings level for the first time.”

Seven states made or authorized withdrawals in fiscal 2020 to prepare for and respond to the budget shortfalls: Arizona, California, Georgia, Iowa, Maine, Nebraska, and Washington.

Georgia, for example, plans to use rainy day funds to close a projected year-end budget gap, but hasn’t made the withdrawal yet.

Arkansas did not make withdrawals from its fund, but established a separate account to help manage coronavirus-related fiscal impacts.

By contrast, several states added to their reserves. West Virginia added $14 million from a year-end surplus into its Rainy Day fund; Maine added $17.4 million to its.

Connecticut deposited an additional $530 million into its rainy day fund, whereas Tennessee lawmakers approved a plan to increase its dedicated savings by $350 million.

Advertisement

Advertisement