(Originally posted in Citizens for a New Louisiana) — While the public debate over carbon capture and property rights continues to heat up, a quiet legislative maneuver may have already tipped the scales. Senate Bill 244, authored by Senator Bob Hensgens, became a sprawling 219-page substitute bill that rewrites vast portions of Louisiana’s energy law and hands sweeping new authority to a single political appointee.

Let us begin this article with a quote from a man who ignited the spirit of American independence from Great Britain.

Government even in its best state is but a necessary evil; in its worst state an intolerable one; for when we suffer, or are exposed to the same miseries by a government, which we might expect in a country without government, our calamity is heightened by reflecting that we furnish the means by which we suffer. — Thomas Paine

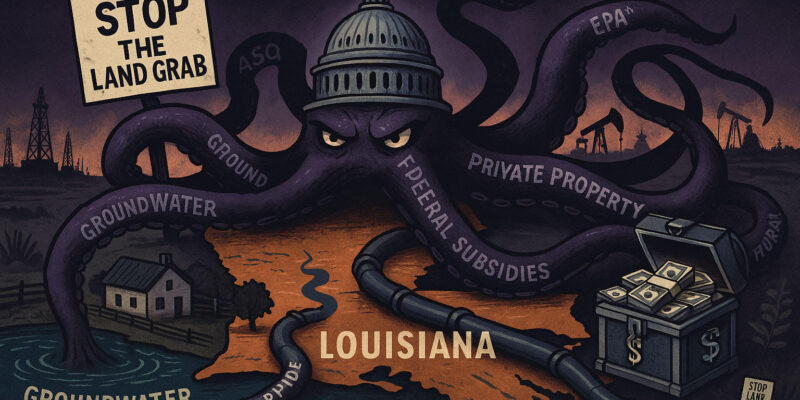

Washington’s Role: The “Green New Scam” Behind the Seizures

The carbon capture craze isn’t just a local fight; it’s a federally subsidized monster fueled by Washington’s budgeting process. No carbon capture industry would exist without federal tax credits and regulatory carveouts. It doesn’t produce a product or generate real demand. It generates transfer payments and real property from taxpayers to corporations and landowners to pipeline developers.

The most egregious of these subsidies is Section 45Q, a federal tax credit that now pays $85 per ton of carbon dioxide captured and stored — a number that industry lobbyists are pushing to raise to $250 per ton. The cost to the U.S. Treasury is staggering:

- $2.4 billion (2022–2026)

- Projected to rise to $30.3 billion by 2032

(Source: U.S. Department of the Treasury estimates, from our earlier article on the topic)

These subsidies are embedded in massive omnibus-style budget reconciliation bills, where energy policy is quietly reshaped behind closed doors.

What Does that Mean for Louisiana?

Roy is talking about the federal budget reconciliation process, where most energy subsidies, including carbon sequestration incentives, are locked in. These bills typically pass along partisan lines using special procedural rules that avoid the filibuster in the Senate.

- Our state laws (like those in SB244) are tailored to attract federal cash, not protect our citizens.

- Projects are greenlit not for economic productivity, but because they unlock billions in federal tax credits.

- Your land, aquifers, and rights are being auctioned off—not to the highest bidder but to the best lobbyist in Washington.

A New Energy Czar

SB244 renames and reorganizes the Office of Conservation into a new Department of Conservation and Energy (p. 6). Instead of being led by a commissioner of conservation, the department would be controlled by a Secretary appointed directly by the governor, centralizing oversight of oil, gas, groundwater, pipelines, injection wells, and mineral leasing under one official (p. 6–7).

This change is more than cosmetic. Throughout the bill, the title “commissioner” is replaced with “secretary,” expanding that individual’s discretion over enforcement, permitting, and regulatory rulemaking (see examples on pp. 7–11, 13–14, 17, and 21).

From Commissioner to Secretary: A Quiet Power Shift

Under current law, the Commissioner of Conservation leads Louisiana’s oil and gas regulatory system. This position has long managed energy development, mineral rights, and environmental compliance.

How It Works Today

- Title: Commissioner of Conservation

- Appointed by: Governor, with Senate confirmation

- Governing Law: R.S. 30:1

- Responsibilities:

- Issuing and enforcing permits (e.g., injection wells, pipelines)

- Overseeing oil and gas drilling, orphan well cleanup, waste disposal

- Protecting aquifers and managing mineral leasing

- Checks and Balances:

- Operates within the Office of Conservation, part of the larger Department of Energy and Natural Resources

- Subject to open meetings, public hearings, and public notice requirements

What SB244 Changes (see p. 6–7)

- Title Becomes: Secretary of the Department of Conservation and Energy

- Appointed by: Governor, still with Senate confirmation

- Term: 4 years, but may serve at the pleasure of the Governor

-

- Full control over a newly created department

- Can delegate duties to sub-offices like “Permitting and Compliance” or “Enforcement” (p. 7)

- May approve expedited permit applications in exchange for extra fees (p. 21)

- Has discretion over public hearings, enforcement timelines, and rulemaking

- Can determine what qualifies as “public convenience and necessity” — a key legal test for eminent domainExpanded Powers:

The New Commissioner’s Role

The commissioner’s role, while appointed, has historically operated with some professional insulation from the day-to-day politics of the Governor’s office. SB244 erodes that distinction. It effectively collapses all permitting and enforcement authority into a single political appointee, with broad discretion and fewer institutional guardrails.

For example:

- Under current law, even controversial projects (like carbon capture pipelines) must go through multiple layers of review and often face statutory limits or technical hearings.

- Under SB244, the new Secretary can:

- Define timelines

- Grant exceptions

- Approve expedited processing

- And potentially greenlight eminent domain approvals — all with minimal external review

In short, it’s Louisiana’s most extensive reallocation of energy regulatory power in decades that few seem to be paying attention to.

Pay-to-Play Permitting

Among the most alarming new powers is a provision for “expedited processing” (p. 21, §30:4(Q)), which allows applicants to pay extra fees to fast-track environmental permits, including those for pipelines and injection wells. While couched as an administrative tool, this creates a tiered permitting system, giving well-financed corporations a significant advantage. And, as we’ve noticed in the current federal budget battle, well-financed most likely means taxpayer-subsidy backed.

Under this model:

- The applicant sets the timeline “agreed to in writing” (p. 8, §30:3(21))

- The department can recover costs plus 20% administrative fees (p. 21 Q.(1)(A)

- There’s minimal accountability — judicial review is confined to the 1st Circuit Court of Appeal (p. 21)

Expanded Authority Over Carbon Capture

SB244 quietly shores up the state’s power to approve carbon dioxide pipelines and storage. It allows the secretary to issue certificates of public convenience and necessity (a prerequisite for expropriation) and to recognize out-of-state carbon injection projects as valid triggers for eminent domain (p. 11, §30:4(C)(17)).

This reinforces concerns that House Bill 601 and HB4 were created to address: Louisiana law already favors corporations over landowners, and SB244 further cements that imbalance.

Regulatory Loopholes and Weakened Oversight

The bill also modifies how public hearings are triggered for new commercial disposal wells (p. 10–11), streamlines site abandonment procedures (p. 12–14), and even permits exceptions to environmental clean-up requirements if the secretary deems them “extraordinarily onerous” (p. 14).

The bill outlines a token public notice process for new solution-mined caverns in Iberia Parish, which sits atop sensitive salt domes. Still, it keeps the final call in the secretary’s hands (p. 20).

The Bigger Picture

The carbon capture debate is about more than pipelines and tax credits. With SB244, the state is restructuring how natural resources are governed and who decides.

It’s a bureaucratic reshuffle that could easily go unnoticed. But the consequences are enormous: centralized power, fast-tracked industrial permitting, reduced public input, and increased vulnerability to abuse.

If the Legislature is serious about protecting landowners and upholding constitutional limits on government power, it must scrutinize this bill’s contents.

Advertisement

Advertisement