In the early hours this past Monday morning the city went forward to fulfill Mayor Mitch Landrieu’s crusade to remove four large Civil War era monuments from public view, by disassembling and hauling away the especially controversial Battle of Liberty Place monument.

While the Robert E. Lee, PGT Beauregard, and Jefferson Davis statues commemorate Civil War figures, the Liberty Place monument memorializes something that happened almost ten years after Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Courthouse.

The Times Picayune describes the Battle of Liberty Place as follows: “Incensed by the presence of blacks in government after the Civil War, members of the white supremacist Crescent City White League in 1874 stormed the U.S. Custom House, where seven New Orleans police officers were killed.”

That’s a convenient narrative for the Times Picayune, which is owned by Advance Publications- a Staten Island, New York based media company, and a consistent if not fervent amen corner for Mayor Landrieu’s historical bowdlerization campaign.

However the local media nor the city ever discuss in any detail what triggered the battle, instead repeating the company line of confederate bigots hunting down black cops.

In 1872, Louisiana was still locked in Reconstruction, one of the ugliest periods of American history as the former rebellious states were treated as if they were conquered territory in a foreign land.

Most of the southern states ceased to be and had to go through a process of being readmitted to the Union, which is ironic since the Civil War was initially fought over the question of whether states had a right to secede in the first place.

President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation was not issued until January 1, 1863 – over a year and a half after Fort Sumter was bombarded. And even then President Lincoln’s directive did not free all slaves, but just those in rebel-controlled areas.

One of the trademarks of Reconstruction was rigged elections that allowed Northern profiteers connected to the men running Washington to take over most of the governments of the defeated states. They secured their positions not with ballots but with bayonets, as they were backed by the Union occupying forces.

Most of the Reconstruction governors of southern states were born in northern states such as Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Maine.

In 1872 Louisiana had an election for governor and state offices.

The contest would be controversial and questionable even by Louisiana standards.

Both the local Democrats and the Republicans, a fusion of northerners and freedmen, claimed victory. The state election return board certified the Democrats as the winners yet Republican gubernatorial nominee William Pitt Kellogg refused to accept the results and as his faction had control of the metropolitan police and artillery, claimed possession of the state government.

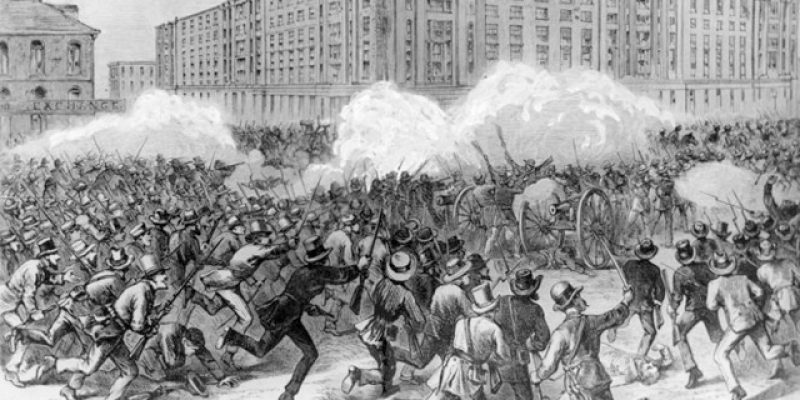

For a period, Louisiana had two governments – one recognized by the locals and one recognized by Washington. Eventually the Democrats had enough of the farce and took action to remove the Kellogg Administration. The ensuing battle that transpired near the foot of Canal Street between the Democratic militia, which called itself the White League, and the Republican militia, the Metropolitan Police force commanded by Gettysburg veteran and ex-Confederate General James Longstreet.

The Democratic militia prevailed in the engagement but later surrendered control of the state government back to Kellogg after Federal soldiers arrived.

Louisiana would find itself in a similar situation in 1876 when both parties claimed to have won the governorship and once again rival state governments were established, though this occasion would play out differently.

In a twist of history, Reconstruction would come to an end because of a political deal: Reconstruction Republican governors in southern states stole the 1876 presidential election for Rutherford Hayes. As the election would be rightfully challenged, a settlement was reached by which Hayes agreed to finally allow self-government in the south by ending the military occupation.

Most southerners with a sense of history don’t regret that the Confederacy lost the Civil War; they do resent Reconstruction, whose excesses paved the way for the rise of reactionary politicians who sowed the seeds of the bitter harvest of Jim Crow, a stain on the region and a terrible burden upon generations of black southerners.

What happened at Liberty Place wasn’t a bid by ex-Confederates to restart the Civil War (as one history-challenged licensed tour guide put it) but a gang fight between two well-armed parties vying for power by undemocratic means, one attempting to depose an illegitimate government that had been installed through a rigged election, the other a cabal desperately trying to keep the White League out of power by any means necessary.

There were no saints on either side of this battle between local white supremacists and usurping interlopers.

While the promotion of the supremacy of any race ought to be discouraged in society, that obelisk was a milestone of our state’s story and a witness to an uncomfortable chapter of American history.

It had ceased to be anything else many years ago.

To tolerate the existence of something is not the same as celebrating it; that’s an important distinction that gets lost in the shouting, vandalism, slandering, and circulation of historically incomplete if not outright false narratives by those who purge the past to advance their current political agenda.

Advertisement

Advertisement