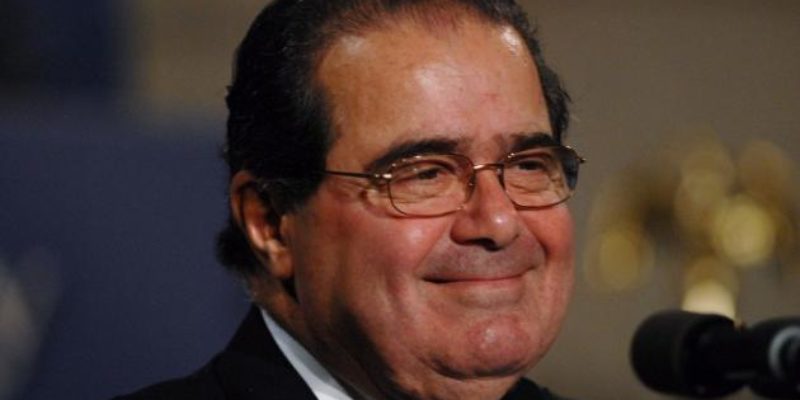

A few years ago, I attended a Continuing Legal Education seminar with retired LSU Law Professor John Baker and U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia. From reading his myriad of dissenting opinions, I expected Scalia to be cantankerous, loud, obnoxious even. Nothing was farther from reality. During the CLE and receptions accompanying it, I found Scalia to be a low-key, mild mannered, extremely pleasant gentleman.

Now that gentlemen is gone. According to news reports, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia died in his sleep while on a hunting trip in Texas. Details are very sketchy, but it appears that Scalia failed to get out of bed this morning and was subsequently found in his bed unresponsive. U.S. Marshals were on the scene at the hunting ranch but no comment has been forthcoming. Stay tuned for more details.

What does this mean for the Court and Country?

To understand what this means for the country, you first must understand Justice Scalia’s philosophy of judicial interpretation. First and foremost, it would be inaccurate to describe his philosophy as a conservative one. It was, rather, one of original meaning. In his view, the proper method for interpreting a law – whether it be constitutional or statutory – was to simply look at the words and ascribe to them their meaning at the time they were enacted, i.e. their original meaning. He expounded on this in a speech to the Catholic University in 1996:

The theory of originalism treats a constitution like a statute, and gives it the meaning that its words were understood to bear at the time they were promulgated. You will sometimes hear it described as the theory of original intent. You will never hear me refer to original intent, because as I say I am first of all a textualist, and secondly an originalist. If you are a textualist, you don’t care about the intent, and I don’t care if the framers of the Constitution had some secret meaning in mind when they adopted its words. I take the words as they were promulgated to the people of the United States, and what is the fairly understood meaning of those words.

This got Scalia into trouble with “living constitution” pushers, who advocated for an “evolving” meaning of the constitution. That didn’t bother Scalia much as opinion after opinion pushed his originalist philosophy.

Similarly, Scalia did not advocate the expansion of so-called constitutional concepts like “substantive due process” because those words did not appear in the Constitution. Scalia didn’t believe that the words of the Constitution covered things like abortion, same-sex marriage, or even the meaning of golf and thus did not believe the Supreme Court had the power to decide such issues.

Again, it is most certainly not accurate to ascribe Scalia’s interpretative position to a conservative vs liberal mindset; after all, Hugo Black was an originalist (among other things). His was simply one of finding what the original words meant, and applying that meaning to the facts at hand.

Not only was Scalia a profound mind with a spot-on interpretive theory, he was also the best, hands-down, at putting his thoughts on paper. His dissents knew no bounds. He made even the most mundane of legal arguments seem interesting. Take these quotes from his dissents, for instance:

- Today’s extension of the Edwards prohibition is the latest stage of prophylaxis built upon prophylaxis, producing a veritable fairyland castle of imagined constitutional restriction upon law enforcement.

- Minnick v. Mississippi, 498 US 146 (1990) (dissenting).

- I find it a sufficient embarrassment that our Establishment Clause jurisprudence regarding holiday displays has come to require scrutiny more commonly associated with interior decorators than with the judiciary.

- Lee v. Weisman (1992) (dissenting).

- As to the Court’s invocation of the Lemon test: Like some ghoul in a late-night horror movie that repeatedly sits up in its grave and shuffles abroad, after being repeatedly killed and buried, Lemon stalks our Establishment Clause jurisprudence once again, frightening the little children and school attorneys of Center Moriches Union Free School District. Its most recent burial, only last Term, was, to be sure, not fully six feet under: Our decision in Lee v. Weisman conspicuously avoided using the supposed test but also declined the invitation to repudiate it. Over the years, however, no fewer than five of the currently sitting Justices have, in their own opinions, personally driven pencils through the creature’s heart (the author of today’s opinion repeatedly), and a sixth has joined an opinion doing so. The secret of the Lemon test’s survival, I think, is that it is so easy to kill. It is there to scare us (and our audience) when we wish it to do so, but we can command it to return to the tomb at will. Such a docile and useful monster is worth keeping around, at least in a somnolent state; one never knows when one might need him.

- Lamb’s Chapel v. Center Moriches Union Free School District, 508 U.S. 384, 398-99 (1993) (concurring) (citations omitted).

- The Court today finds that the Powers That Be, up in Albany, have conspired to effect an establishment of the Satmar Hasidim. I do not know who would be more surprised at this discovery: the Founders of our Nation or Grand Rebbe Joel Teitelbaum, founder of the Satmar. The Grand Rebbe would be astounded to learn that after escaping brutal persecution and coming to America with the modest hope of religious toleration for their ascetic form of Judaism, the Satmar had become so powerful, so closely allied with Mammon, as to have become an establishment of the Empire State. And the Founding Fathers would be astonished to find that the Establishment Clause — which they designed to insure that no one powerful sect or combination of sects could use political or governmental power to punish dissenters — has been employed to prohibit characteristically and admirably American accommodation of the religious practices (or more precisely, cultural peculiarities) of a tiny minority sect. I, however, am not surprised. Once this Court has abandoned text and history as guides, nothing prevents it from calling religious toleration the establishment of religion.

- Board of Ed. of Kiryas Joel v. Grumet (1994) (dissenting)

- [I]t is not of special importance to me what the law says about marriage. It is of overwhelming importance, however, who it is that rules me. Today’s decree says that my Ruler, and the Ruler of 320 million Americans coast-to-coast, is a majority of the nine lawyers on the Supreme Court. The opinion in these cases is the furthest extension in fact—and the furthest extension one can even imagine—of the Court’s claimed power to create ‘liberties’ that the Constitution and its Amendments neglect to mention. This practice of constitutional revision by an unelected committee of nine, always accompanied (as it is today) by extravagant praise of liberty, robs the People of the most important liberty they asserted in the Declaration of Independence and won in the Revolution of 1776: the freedom to govern themselves.

- Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) (dissenting)

What does all of this mean for the Court and the Country?

First, Clarence Thomas is the only true originalist on the court. Other “conservative” justices sometimes have fits of originalism, and, more often than not reach the right result. But none have that pronounced originalist intent of Scalia and Thomas.

Second, you can count on the “conservatives” to lose more than they otherwise would have. There are many reasons for this, including that, primarily, Scalia will not be there to add his vote to the conservatives. Further, the ominous threat of a Scalia dissent is thought to have been a moderating force among the liberals (and especially Anthony Kennedy), and it now disappears.

Third, don’t expect Scalia to be replaced any time soon. As Ed Whalen at National Review noted, “It’s been more than 80 years since a Supreme Court justice was confirmed in an election year to a vacancy that arose that year, and there has never been an election-year confirmation that would so dramatically alter the ideological composition of the Court.” The Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committe, Chuck Grasley, has already set forth his position that a nomination should not be taken up until after the November election. Plus, we have some good conservatives on the committee like Vitter and Cruz. Look for a lot of debate, but no action.

Interestingly, the Senate is currently in recess and Obama could use his recess appointment power of Article II, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution to replace Scalia before the Senate reconvenes on February 22. This is tricky for Obama not only because of the political firestorm it invites but also because he would have such a short time to find a qualified candidate. Further, the appointment would only last through the end of the current term (roughly the rest of this year) before the appointment would end and the seat would be vacated again.

Finally, the long-term balance of power on the court depends on the next President. Elect a President who will replace Scalia with someone who thinks like Scalia, and the disruption of the current balance of power should be minimized. Elect Bernie, and you can kiss a sane court goodbye.

As it turns out, the American people will have a large hand in selecting the next justice. And, in my view, that probably suits Justice Scalia just fine.

Advertisement

Advertisement