Mask-making has become a literal cottage industry over the last month as a means of warding off coronavirus.

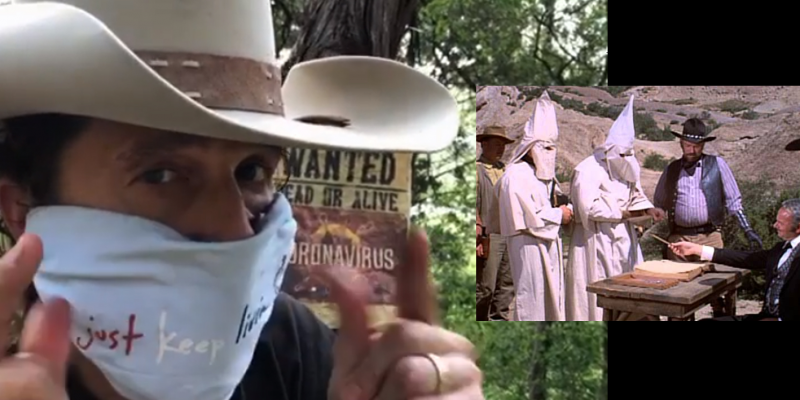

Makeshift facial protections are so en vogue lately, even actor Matthew McConaughey as “Bobby Bandito” jumped on the bandwagon showing how to make a face filter from a bandana and a coffee filter. Now everyone looks like a bandanna bandit walking into essential stores and businesses, whereby in normal times they would be suspected of being the kind of robber McConaughey was channeling in his instructive video.

It’s for that reason the Governor of Georgia stepped in and said it’s okay to wear a mask, even though state law forbids it.

On Monday, Republican Gov. Brian Kemp declared a pandemic exemption from a 1951 state law that prohibits wearing masks in public after some black officials warned that some African Americans, fearing harassment by police, might not cover their faces for protection.

The anti-mask law makes it a misdemeanor to wear “a mask, hood” or other face covering to “conceal the identity of the wearer” on public property. Georgia passed the law to prevent [Ku Klux] Klan members from wearing hoods during public rallies and marches. With the federal Centers for Disease Control now encouraging Americans to wear masks that cover the mouth and nose in public, Kemp signed an order Monday that says the anti-mask law can’t be enforced against people covering their faces as protection against the virus.

See the rest of the story from US News and World Report here.

Gov. Kemp’s declaration allows citizens to wear masks. But in Texas, several municipalities have recently issued orders requiring masks to be worn. And come to find out, mask laws — particularly throughout the South — are a patchwork of conflicting standards.

In Austin, a mandate was handed down by the city and Travis County that anyone in public over the age of 10 must wear a protective face mask. As with the previous issuance of the shelter-in-place order, numerous carve-outs were put into place. These exceptions can be made for when people are exercising, are outside only with members of their household or are eating or drinking. The legality of the order was questioned, and the Austin Police are already announcing that it will mostly expect voluntary compliance.

Unlike Georgia, Texas allows for masks. The Lone Star State attempted an anti-mask law in 1925, when then-Governor Miriam Ferguson pushed for and signed a law intended to forbid members of a resurgent Ku Klux Klan from wearing hoods or masks to protect their identities. The Texas Supreme Courts soon overruled it.

It appears Texas and Georgia are not the only states which have struggled with the legal consequences of mask laws.

Activists of the extreme Left or even the alt-Right have been known to wear masks to conceal their identity, be they bandannas or Guy Fawkes masks. A 2017 protest surrounding an ill-fated Milo Yiannopoulos speech at the University of California, Berkeley, featuring thousands of protesters with face coverings prompted the New York Times to do a little digging and a reporter noticed a distinct disparity from how masks are approached in California versus throughout the South and in other places:

Some conservative media sites have criticized the University of California for not cracking down on protesters from the left, and have lauded the tough stance taken by the authorities at Auburn University in Alabama. Before a speech by the white nationalist Richard Spencer at the Auburn campus …, the police stopped anti-fascist [sic] protesters and ordered them to remove their masks.

… The different approaches by the police at Berkeley and Auburn illustrate more than just a contrast in tactics to try to tame clashes between far-left and far-right demonstrators. The authorities in Alabama also have a law enforcement tool that those in California lack: a broad anti-mask law.

… Alabama has had an anti-mask law on the books since the 1940s, with many exceptions such as Halloween and Mardi Gras celebrations.

The Times noted that Ohio has a law that makes it illegal for two or more people to wear “white caps, masks or other disguises” while committing a misdemeanor.

In West Virginia, the Times also reported, a broad law prohibits masks except for holiday costumes, winter outdoor gear, and other exemptions.

In New York, a law on the books since 1845 was dusted off to arrest Occupy Wall Street protesters in 2011. The original law was meant to unveil land dispute protesters who dressed as American Indians to obscure their identities, the Times reported.

Motorcyclists wearing bandannas or other face coverings have found difficulty traveling from jurisdiction to jurisdiction in which laws differ, particularly in Louisiana where a strong anti-mask law carries a six-month to three-year term of imprisonment.

Advertisement

At least 10 other states have anti-mask provisions on the books. But California is a whole other situation.

In 1979, Iranians began seeking asylum in California following the Shah’s seizure of power, leading some to complain that masks conceal their identities so that their families back in the Middle East are not the victims of retribution attacks. Thus, the Golden State’s mask ban was soon struck down by the state courts.

(As a side note: Before the Iranian revolution, it was not mandatory for women to wear the hijab covering — but in the U.S. many female adherents to stricter forms of Islam have found difficulty wearing head or face coverings for religious purposes, with state anti-mask laws being a factor and often conflicting with religious freedom legislation.)

California isn’t the only place where masks have been allowed for civil rights reasons. In Indiana in 1999, a federal district court case awarded the American Knights of the Ku Klux Klan organization in the city of Goshen the right to wear masks in public settings for lawful assemblies.

Tennessee and Florida have also invalidated their anti-mask laws on civil rights grounds.

From the hip: Anti-mask laws, while originally intended to curtail violence, are often challenged on the grounds that they protect the First Amendment’s right to freedom of assembly and petition.

These laws can serve as an example of how, in the throes of a public safety concern, civil rights can be easily taken away in the name of pragmatism. Rights are also often taken away because of political pressures — what legislator wants to run for re-election having been one of the few of his peers to oppose a law designed to push back against the Klan? Isn’t that how we ended up with t̶h̶o̶u̶g̶h̶t̶ ̶c̶r̶i̶m̶e̶ hate crime laws on the books in so many places (though incredibly difficult to enforce and fully prosecute)? It’s all about the feels.

Georgia’s situation is unique in that, after decades of being invalidated by lower courts, the state Supreme Court found the anti-mask law constitutional — only to require further clarification by the governor. The court’s logic was that the wearing of a mask amounts to an act of intimidation and a threat of violence, which was not deemed protected speech. But this song-and-dance routine is what happens when a law is passed without a 360-degree view to the potential consequences. The same goes for quickly hobbled together orders declaring what businesses and institutions are “essential” and “non-essential,” which we’ll hear a lot about today as states begin implementing their phase-ins of which entities are allowed to re-open amid dwindling COVID-19 cases.

____

Image credit: Screenshot of McConaughey’s YouTube video, promotional screenshot from scene in “Blazing Saddles.”

Advertisement

Advertisement