At a time when the national debt is $27 trillion—the largest it’s ever been—the least we can do is make sure that government relief payments are going to people who need them most.

Unfortunately, too much of that money is ending up in the hands of fraudsters who capitalize on the deaths of their fellow Americans.

The problem isn’t new. Every year, the federal government sends taxpayer dollars to dead people. Ghosts can’t cash checks, but fraudsters can, using the bank accounts of deceased friends and relatives as their own personal ATM machines.

Just last spring, the government sent coronavirus relief checks worth nearly $1.4 billion to deceased Americans. Congress has since acted to try to limit the damage, but many people who died in 2020 still likely got a $600 check from December’s round of coronavirus payments.

The struggle is perennial. In 2018, the Social Security Administration (SSA) sent checks worth $40 million to dead people in Maryland, Michigan, and Texas. Who knows how much more was lost in the other 47 states?

Sadly, the IRS is very limited in what it can do to claw back improper payments. It can ask politely for the money back, but it’s unlikely that people who mistakenly believe the money is due them or those who are comfortable committing fraud will return the payments.

Recovering the money legally can be a pricey pursuit in itself, and that process could add to the grief of families who have lost loved ones and now find themselves in a bureaucratic mess of the government’s making.

Specifically, the government’s incredibly flawed bookkeeping and administration are to blame. Social Security keeps a database of all deceased Americans, but the SSA refuses to share it with most federal agencies, including those that write checks.

Most federal agencies just rely on their own incomplete, outdated list. It’s no wonder the Treasury sends money to the dead: They simply don’t know any better because one government agency won’t talk to another.

Fortunately, the Senate took decisive action to fight back against this practice by passing the Stopping Improper Payments to Deceased People Act unanimously, and President Trump signed an improved version of this bill into law this December.

A result of bipartisan, bicameral agreement, this new provision of law requires the SSA to share comprehensive death data, including the most up to date state-reported list, with the Treasury’s Do Not Pay Program.

When they no longer have to rely on incomplete data supplied by the SSA, federal agencies that interface with the Treasury will have the information they need to avoid sending improper payments to Americans who are no longer living.

Advertisement

These measures will save taxpayers billions of dollars, but we should do more. The SSA relies on contracts with states to receive and share each state’s death data. Before this new law can be truly effective, the current contracts will have to expire.

That means the bill’s full effects will not come into play for about three years. Absent executive action to void and renegotiate these contracts, billions of dollars will continue flowing into dead people’s pockets—at the expense of American workers and families who are still suffering under a pandemic.

President Joe Biden has said he wants to be a unifying president. Well, now’s his chance to make the most of a winning issue. No taxpayer, regardless of party, is likely to support sending taxpayer money to dead people.

The president has a rare opportunity to act now to fix this problem ahead of schedule, saving billions of dollars over the next few years. Millions of Americans have lost their livelihoods during the coronavirus pandemic.

If the Biden Administration’s top priority is to save lives and jobs, it must stop playing into the hands of fraudsters.

Even in a polarized political climate, we can all agree that government shouldn’t be redistributing wealth to the dead.

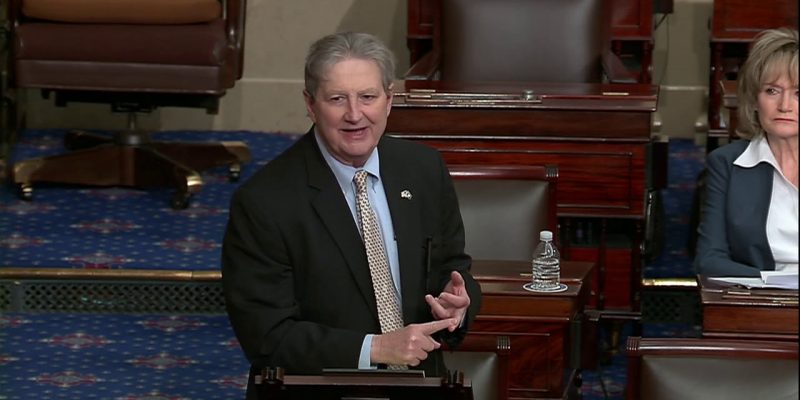

Sen. John Kennedy, R-La., is on the Senate Banking, Budget and Small Business committees, and is the ranking Republican on the Appropriations Subcommittee on Energy and Water Development. This post originally appeared at CNBC.

Advertisement

Advertisement