The U.S. Supreme Court gave its strongest indication yet that it would rework, if not abandon, reapportionment jurisprudence that increasingly has pushed creating maps where the proportion of representatives mirrors the proportion of racial minorities in the population – based on a Louisiana case that also would affect Louisiana cases at other levels of government.

The first shoe dropped when in late June the Court issued a statement it would rehear Louisiana v. Callais, an appeal to a ruling that the state’s congressional districts had been drawn impermissibly on the basis of race and the only case it heard all year on mandatory appeal, this fall. Assoc. Justice Clarence Thomas dissented, saying the facts were clear and that the Court shouldn’t avoid addressing conflict between current Voting Rights Act judicial interpretations and the Constitution about to what extent race could be used as a criterion in apportionment.

Thomas got his wish when the other shoe dropped last week. The Court scheduled submission of briefs essentially asking that question. Further, it did it on a timeline that portends the hearing with that additional question at the start of its term, which could set things up for an early decision in time to govern the 2026 election cycle for the state.

Keep in mind that this isn’t a situation where nine justices were sitting around a month or so ago pondering whether such a conflict existed and then took five weeks to figure out they wanted more input to help them make up their minds. When the Court does something like this, they have made up their minds already to a man or woman on that question and the majority wants to settle the issue, thinking that the briefs may give them additional ammunition to construct their arguments.

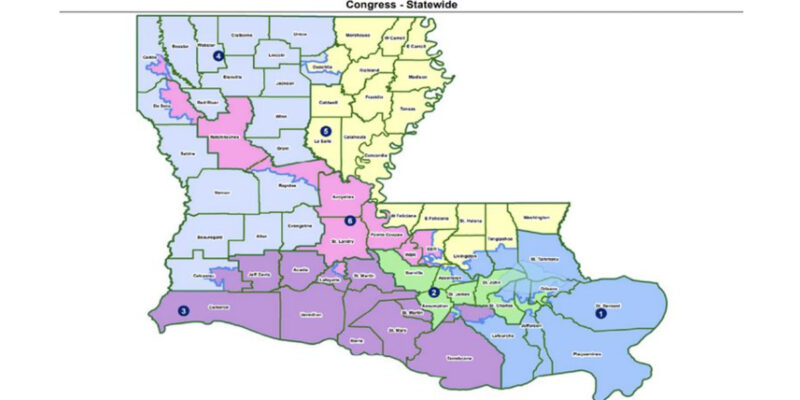

And, given the run of jurisprudence even from the last case it decided on the topic in 2023 that strengthened giving race preference over other reapportionment criteria which included a concurrence from Assoc. Justice Brett Kavanaugh broaching revisiting it, very likely it seems that this preferred position will be stripped away, if not the entire ability to use race at all except as a remedy for intended discrimination. Since Callais deals with the state’s congressional districts – disputing the forced two of six being majority-minority – declaring that map unconstitutional and in the process dispatching the expansive interpretation of the VRA not only would invite the state to go back to a plan with a single M/M district, it also would affect ongoing litigation at the state legislative and local government levels.

Nairne v. Landry contests the drawing of state legislative districts, using the same proportionality logic, and to date has produced a district court ruling that these violate the VRA. Schizophrenically, in this case Louisiana argues against that calculus using precisely that view that the VRA impermissibly conflicts with the Constitution which it conspicuously avoids making in Callais where it’s on the other side of the fence. The signaled outcome in Callais would end Nairne immediately and leave the current legislative maps in place.

Means v. DeSoto Parish concerns an even greater elevation of race over other criteria. There, up to the last reapportionment cycle the Police Jury had over 40 percent of its population identifying at least in part as black, which resulted in a map with five of 11 M/M districts, but then after the 2020 census that proportion fell to 36 percent but the enacted map maintained five M/M districts only through an aggressive racial gerrymander that clearly violated other criteria. The expected direction of Callais if that occurs would feed into a contemplated February trial that would declare the existing arrangement unconstitutional and set the stage for a new map’s implementation, whether by the Jury or court, in time for 2027 elections.

That’s just the litigation. Of course, any such ruling would affect all executive and legislative reapportionment in every jurisdiction, where it could be expected that partisan gerrymandering would intensify as long as it generally adhered to other criteria of reapportionment, such as having reasonably compact districts, absolutely contiguous ones, and to a large degree easily-defined communities of interest intact.

While it’s possible that the Court uses Callais to define more fully when race may predominate in mapping, as things stand Louisiana should expect to be the epicenter of a momentous shift in reapportionment jurisprudence.

Advertisement

Advertisement