We’re beginning to see a bit of attention paid to stories like this…

Dominion’s Cove Point liquefied natural-gas terminal was originally built to receive natural-gas imports. But with the U.S. boom in natural-gas production, Dominion, Cheniere Energy Inc. (LNG) and other companies have sought to modify their terminals to export natural gas abroad, where prices and demand are higher.

“With all the gas that’s available in this country now, particularly in this region, we think it’s likely the permit will be issued [and] we expect to have it later this year,” Dominion Chairman and Chief Executive Thomas Farrell said during a conference call with analysts to discuss fourth-quarter earnings.

Last autumn, the company applied with the U.S. Department of Energy to export up to 365 billion cubic feet of natural gas from the terminal, and has been in discussions with potential customers in Europe and Asia, and with U.S. natural-gas producers, about deals, Farrell said.

The facility in question is in Maryland, and it’s perfectly suited to hook up with the Marcellus and Utica natural gas fields in Pennsylvania, New York, Ohio and West Virginia. Dominion Resources expects that they’ll be able to load a billion cubic feet of natural gas a day at Cove Point when it’s all said and done. But Dominion’s plans are small potatoes compared to the other projects out there.

For example, Cheniere Energy has already announced plans to upgrade their Sabine Pass facility here in Louisiana to accommodate natural gas exports – specifically by gaining the capability to perform liquefaction of the gas. The upgrade was announced back in July…

“Once liquification is taking place and the plant expansion is operational Cheniere will be able to export to ships and import as well. Bottom line we will have one of the first bi-directional facilities right here in Louisiana,” said Gov. Jindal.

The Sabine Pass project is a $6 billion investment and it’s expected to be up and running as an export terminal by 2015. While Cove Point will export Marcellus gas, Sabine Pass will export Haynesville Shale product to the world market. And Sabine Pass will export up to 2.2 billion cubic feet of natural gas per day when it’s fully operational.

In total, there are nine companies in front of the Department of Energy seeking permission to set up LNG export facilities and move natural gas to foreign consumer markets in places like Europe and Asia – if all the permits go through as much as 12 percent of current natural gas production could be headed overseas. The Europeans are desperate to find a supplier of natural gas not named Russia, as the gangster mentality of Moscow has made for problems not just economic but political as well. And in Asia, a lack of domestic supply makes for hungry customers.

In fact, world natural gas prices are significantly higher than here in America. A few charts to peruse…

As you can see, prices for natural gas in Japan and Europe are rising and greatly outpace domestic prices here in America.

And in Europe, demand will only rise – particularly as the Euros allow environmentalist fear-mongering to poison their coal and nuclear power industries. This chart projects a major shortage of natural gas going forward unless another supply is found…

Meanwhile, domestic natural gas prices are in the dumpster – and there isn’t much indication they’ll improve in the near term…

Natural gas’s worst start to a year since 2001 has the most accurate forecasters predicting further price declines as surging U.S. shale production threatens to overwhelm the nation’s storage facilities.

Prices may drop below $2 per million British thermal units (Btu) for the first time since 2002 amid the prospect of stockpiles exceeding storage capacity in October, according to Bank of America, Barclays Capital and Prestige Economics.

Inventories will probably end March at 2.15 trillion cubic feet, an all-time high for that time of year, Bank of America says.

“If we exit the winter with such high levels of inventories, there’s a real risk of gas prices coming down very sharply in the fall,” said Francisco Blanch, the head of commodities research at Bank of America in New York and the most accurate forecaster of U.S. gas ranked by Bloomberg in the eight quarters ended Dec. 31. “Gas production has to come down,” he said in a phone interview Jan. 13.

Current prices aren’t that far from $2 as it is…

Gas production grew by a record 4.5 billion cubic feet a day in 2011, the Energy Department said in a Jan. 10 report, while demand lagged behind at 920 million.

Natural gas for February delivery rose 2.9 cents to $2.554 per million Btus on Tuesday in New York. Gas, which is down 44 percent from a year ago as warmer winter weather saps demand, fell to $2.231 on Jan. 23, the lowest price since February 2002.

And of course the development of fracking and horizontal drilling, and the opening of shale gas as a resulting abundant energy resource, means either a fizzling of an industry which could be worth hundreds of thousands if not millions of American jobs or a major glut in domestic supply which will have to be remedied in some fashion.

There are several ways to use all this extra natural gas.

First would be to develop it as a transportation fuel, and that’s probably the best solution. By getting an increasing segment of the nation’s vehicle fleet to run on compressed natural gas (or LNG, depending on the size of the vehicle) you replace imports of foreign oil, create price competition between the oil refiners and natural gas producers to the benefit of the consumer (competition which might be best analogized with that between cable companies and DirecTV) and reduce scarcity in the energy market since our natural gas supply looks virtually inexhaustible at present.

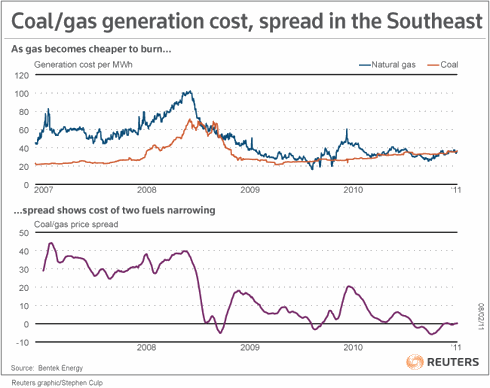

Second would be to build natural gas power plants on virtually every street corner. Which makes quite a bit of sense, given that natural gas is a much cleaner-burning fuel than coal and costs about the same – here’s a graph to demonstrate that…

What’s more, the cost of building a natural gas power plant is about half that of a nuclear plant, according to Exelon Corp. CEO John Rowe.

The problem with both of these two solutions is that they’ll both take time. The permit-approval-construction process for a natural gas power plant requires years of lead time, and it’s impossible to know when a transition away from the current gasoline-dominated transportation fuel market into something which includes natural gas would get underway.

But exporting natural gas, which is the third major option, is something which can be done rather quickly – and, for the natural gas producers now sitting on more product than they can move, and who are currently scaling down operations as prices take a dive in America while they climb in the rest of the world, quite profitably.

This should, therefore, be a no-brainer. Believe it or not, it’s actually controversial…

One of the strongest arguments in favor of drilling for Marcellus and other shale gas in the U.S. is that it provides a cheap alternative fuel for Americans—a “home grown” energy source that benefits everyone. It’s a simple and undeniable fact: Cheap energy translates into economic prosperity for all citizens. Cheap energy makes it easier for businesses to produce goods and services, and that means jobs.

Energy companies often make the “cheap domestic energy” argument when talking about the benefits of shale gas drilling—rightfully so. But when those same companies then start exporting natural gas, well, it’s a tad hypocritical. Exporting leads to less supplies here at home, and less supplies means higher prices. Energy companies will argue we have more than enough—an excess of natural gas—and by exporting they create more jobs here at home. But others (like MDN) are not so sure that argument holds up, especially for a nascent industry with huge potential to transform the energy picture here at home.

The primary groups screaming about the potentiality of natural gas exports are utilities who’d like to keep the natural gas producers under their thumbs…

There’s little doubt that exports will cause the price of natural gas to rise. The debate is whether the rise in gross domestic product and gas field employment might offset the negative effects of higher domestic energy prices.

“I don’t think anybody knows the answer to that question, which we think argues for slowing down these (export) facilities,” said Dave Schryver, executive vice president of the American Public Gas Association, a trade group for municipal gas utilities.

“Until you have a strong, accurate view of what the impact is going to have on consumers, it’s premature.”

Naturally, this is likely to be a higher-profile issue as time goes by and politicians get involved, and given the track record of those politicians in resorting to demagoguery every time strategic issues of energy come up it’s inevitable that something which ought to be obvious result in the market – we have all this natural gas, so until we find out a way to profitably use it here we’ll just export what we don’t need to folks who will pay top-dollar for it – you can bet this issue will become distorted.

And that’s not necessary. A smart energy policy could all but wipe out our trade deficit, make our energy costs (to include transportation) a fraction of what the rest of the world must pay, make this the friendliest country on earth for manufacturing and insulate us from price shocks on the global market.

We haven’t had a smart energy policy for decades, though, so nothing can be taken for granted.

Advertisement

Advertisement