Two of the most important dynamics in politics are timing and luck.

Sure, money helps, as does political machine support. But, as in economics, there’s a point of diminishing returns in politics as well.

And even a political machine can only do so much. There’s an old saying in Hollywood that you can’t stop people from not seeing your movie.

Sometimes people just won’t buy what you’re selling.

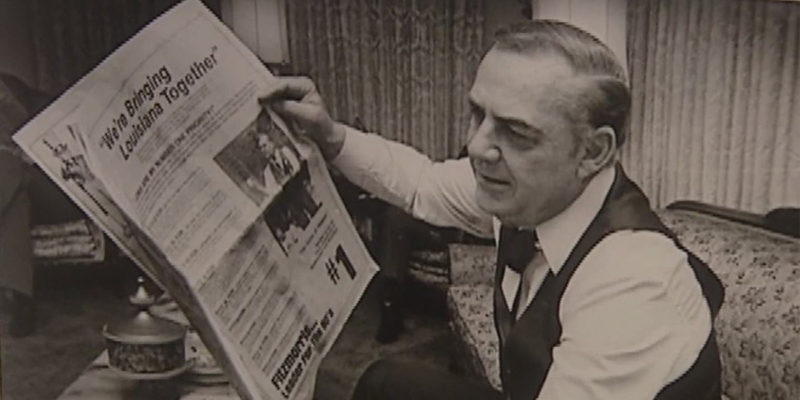

The late Jimmy Fitzmorris learned these lessons all too well in his two bids for mayor of New Orleans.

In 1965, then-Councilman Fitzmorris sought to unseat Vic Schiro.

If the always smiling Fitzmorris was a ward politician from central casting, Schiro was the ultimate caricature of a New Orleans politician. Physically unimposing, balding, and mustachioed, Schiro could’ve starred in one of the Frankie & Johnny furniture commercials encouraging customers with credit issues to see the “special man.”

Added to this mix were Schiro’s legendary malapropisms and other odd declarations.

Schiro’s most (in)famous was “Don’t believe any false rumors unless you hear them from me” as the city flooded during Hurricane Betsy.

But such instances led to Schiro being underestimated, as he was a cunning politician. The mayor convinced President Lyndon Johnson to visit the Ninth Ward to immediately survey the catastrophe and closed out the campaign while recovering from an appendectomy in a bathrobe announcing the future construction of the Superdome.

Also contributing to Fitzmorris’s defeat by a mere 3,319 votes was the perception that he was too progressive at a time where New Orleans was still a fairly conservative city.

Ironically enough, the reverse problem would take Fitzmorris down four years later. Despite having a 15 point lead over Moon Landrieu in the primary, Fitzmorris was now viewed as too conservative in a rapidly changing city, as the suburbs began to grow, creating a vacuum filled by nascent black political organizations. Though New Orleans was predominantly white, black voters proved decisive in electing the patriarch of a future political dynasty.

Coming off two competitive losses, Fitzmorris would salvage his political career running for the vacant lieutenant governor’s post.

Instead of being hurled into political oblivion, Fitzmorris would post two strong statewide wins and with Edwin Edwards and Moon Landrieu termed out of their respective offices Fitz had to make a decision: take a third stab at leading his hometown, or go for the state’s top office.

Fitzmorris made the wrong call, perhaps haunted by his previous loss for City Hall and over-confident from his big wins for lieutenant governor.

There are two other dynamics that would manifest themselves in the 1979 gubernatorial election: first, a change in political system and secondly, a thumbing of the electoral scales.

One of Edwards’ legacies in Louisiana was the open primary, a reaction to having slogged through two taxing statewide campaigns to secure the Democratic nomination for governor and then to have to face an unscathed and well-financed Republican opponent in the general election.

EWE resented this advantage by Republicans and engineered the open primary that Louisiana still operates its elections under.

Ironically Edwards has said it was the biggest mistake of his political life as it led to the growth of the GOP in Louisiana.

However nobody could resent it more than Fitzmorris, who fell victim to this novel shift in the political landscape.

As Republican Party voter registration was still “fun sized” in the 1970s, conservative Democrats supported Republican Dave Treen in the primary. Had there been a Democratic primary and not an open primary, those same voters would’ve likely broken heavily towards Fitzmorris.

As the spike in Jefferson, St Tammany, and St Bernard Parishes deprived Fitzmorris of the conservative former Orleans Parish voters he needed against Landrieu in 1969, the open primary bled to Treen those same Democrats he needed to make a runoff.

Advertisement

Or did Fitzmorris actually win just enough to face Treen in the second round?

On election night Fitzmorris was projected to finish second and likely dispatch the Metairie Republican congressman in the runoff, as the Democratic vote would have coalesced around Fitzmorris.

But overnight there was a shift in votes that mysteriously moved Public Service Commissioner Louis Lambert, who was the liberal candidate, just ahead of Fitzmorris.

Fitz smelled a rat and his team launched an aggressive investigation into shenanigans that ranged from voter machine manipulation to more votes cast than signatures in the precinct rolls to outright vote buying. Unfortunately for Fitzmorris, his legal challenges to overturn the election went nowhere.

While Louisiana has a well-earned reputation for shady elections, the 1970’s proved to be a particularly egregious decade for cheating and other gross election irregularities. Congressional races in the Sixth (1974) and First (1976) Congressional Districts had to be rerun and an investigation in the Shreveport district (Fourth) in 1978 brought to light illegal practices that doomed the reelection prospects of the incumbent.

What happened in 1979 was merely the continuation of a political culture that far too many Louisianans were at peace with as the Fowler family would retain their grip on the Elections Commissioner post since its creation in 1956 by Earl Long until 1999.

By the way, considering Louisiana’s track record for having banana-republic elections there are few books out there that delve into detail about the mechanics of vote theft. Fitzmorris’ autobiography “Frankly Fitz” was a rare exception, and the “Bitter Harvest” chapter that delineates the corrupt happenings in a number of parishes and the questionable dearth of criminal charges filed by district attorneys in those areas is required reading for any student of the Bayou State’s political history.

Though Fitzmorris would not win another campaign, the soon to be ex-lieutenant governor would figure prominently in an historic election.

Though a Democrat, he and the other major Democrats who did not make the runoff united behind Treen and worked hard to elect Louisiana’s first Republican governor in the 20th century.

Treen won by a scant margin of just over 9,000 votes, but most importantly Fitzmorris provided assistance to Treen’s team to stop the steal in the second round.

For breaking party ranks Fitzmorris was officially censured by the Louisiana Democratic Party and his principled decision to back Treen would cost him dearly in his unsuccessful comeback bid for lieutenant governor in 1983.

Fitzmorris would later chair Democrats for Bush in Louisiana during the 1988 presidential election, though he would remain officially affiliated with the Democrats while his brother Blue Dogs moved on to the GOP.

Though bad timing would cause Fitzmorris to finish agonizingly short of fulfilling his greater ambitions, Fitz would lead a full life and leave his mark on New Orleans, particularly for his role securing much of the land consisting of the Superdome’s footprint, and becoming the first modern lieutenant governor of Louisiana and providing a critical assist in creating a viable two party system in the state.

Advertisement

Advertisement