Editor’s Note: The Hayride is likely to be a bit lean on content for the rest of the week, and there’s a good reason for this although I’d like to apologize nonetheless. I’m working to finish the first draft of The Revivalist Manifesto and send it off to the publisher no later than Monday – and actually I’m really trying to get this done on Friday so as to have the weekend off.

Because of that, it’s long days and late nights adding bits and pieces, snipping them out, editing and scowling over this chapter and that. Most of it is unnecessary, as we’ll have an editing and rewrite process to come involving the pros at Bombardier Books, but having self-published three novels with the forth to come, I’m used to a certain process and standard of quality.

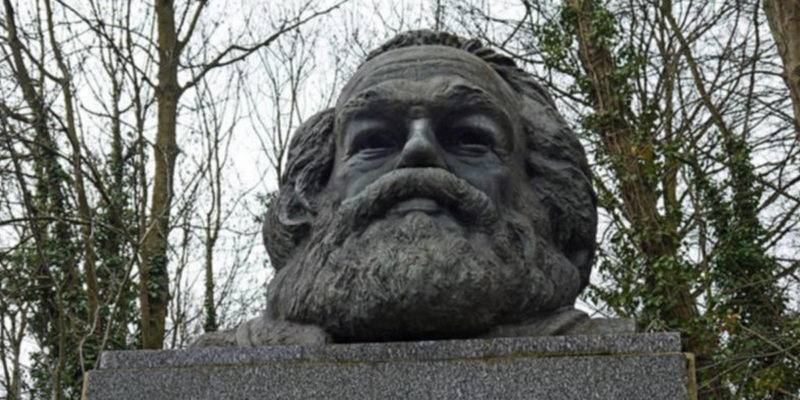

So because I’m likely to be a bit on the silent side for the rest of the week, I thought I’d put this out for your perusal. It’s an excerpt from Chapter 5 of The Revivalist Manifesto, and its subject is one Karl Marx. Enjoy…

One of the enduring failures of capitalist America which will someday, hopefully, be remedied at long last is that the motion picture industry has never made the biopic of Karl Marx that man truly deserves.

I don’t say this from a Marxist perspective, in case you misunderstand. What the modern public needs to see of Marx was what an utter, unmitigated oxygen thief he truly was. If some filmmaker of a conservative or non-Marxist bent were to give Marx the treatment Hollywood has given various conservative or Republican figures – Roy Cohn, Nixon, George W. Bush – there’s a chance the public might get a sour taste in its mouth for a profoundly meritless, degenerate little man whose philosophy reflects his own lifestyle.

Namely, that Marx was a leech, and Marxism is a philosophy for leeches.

We know a good bit about Marxism, seeing as though it gets foisted on us so commonly in our culture, education, and politics, but not as much about Marx himself. So here’s a quick nickel tour for you.

Karl Marx was born in Trier, Germany, in 1818, the son of a well-to-do lawyer from a rich family with extensive landholdings including several vineyards. The Marxes were a Jewish family, from which a long line of rabbis had come, but Heinrich Marx, Karl’s father, was the first with a secular education and he had converted to evangelical Christianity.

Karl was baptized Lutheran, but he converted to atheism. He was sent off to college at the University of Bonn, but amid a marination in radical politics he drank his way out of that school and his father made him transfer to the University of Berlin instead. There he found a bit of direction in life, marrying the daughter of an aristocrat and studying law and philosophy in hopes of finding a way to fuse the two. He dabbled in writing fiction and poetry while again finding society among political radicals and found himself lacking in means after his father died in 1838. By 1842 he was living in Cologne and working as a journalist for a radical left-wing newspaper, Rheinische Zeitung (the Rhineland News).

This wasn’t the most popular place for the young Marx to ply his trade as a writer. The Prussian government was leaning on his employer quite heavily. As he wrote, “Our newspaper has to be presented to the police to be sniffed at, and if the police nose smells anything un-Christian or un-Prussian, the newspaper is not allowed to appear.”

The next year, the Prussian monarchy shut down the Rhineland News following an international incident involving its sharp criticism of the Tsar, and Marx was on the move again. This time he surfaced in Paris as the co-editor of Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher, or French-German Annals. It was a fiery, left-wing radical newspaper, and it hardly lasted a year, especially after Bavarian authorities banned its importation for having issued forth some rather biting satire of King Ludwig. Marx was soon bouncing to another Parisian German-language paper, dead broke with a newborn daughter and a wife giving him the evil eye and frowning upon his life choices.

He spent most of his free time reading books and developing his philosophy, a dog’s breakfast of Hegelian dialectics, French utopian socialism and English market economics. Marx wrote a book titled The Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts in 1844, a boring tome which discussed philosophy at length despite ultimately rejecting the concept that ideas mattered – Marx held that it was physical action which ruled the world.

One is tempted to believe that came from his wife telling him he was a bum and that he needed to get a real job.

Then he met Friedrich Engels. That turned out to be an important moment in Marx’s life, as the German-language paper he was editing at the time had been shut down by the French government at the request of the Prussian king and the French had invited him to hit the road. Marx took the family to Brussels, where he was granted asylum on condition that he publish nothing about contemporary politics, and Engels, who was a German socialist writer in his own right, settled in that town as well.

Marx and Engels hit it off, and by the summer of 1845 they’d made their way to England at the invitation of a leftist group called the Chartists, for whose newspaper Engels had found employment writing and editing. With Engels’ help, Marx wrote his second book The German Ideology, the major thesis of which was that materialism was essentially the sole driver of human conduct and using that as the basis of “scientific” socialism.

It’s all about them deutschemarks, y’all.

The German Ideology wasn’t published until 1932 thanks to government censors in several European countries giving it a profound “Hell, no.” And in 1847 Marx tried again, writing a book titled The Poverty of Philosophy which was intended to mobilize the proletariat to make a revolution and change society.

Marx and Engels were then involved in a secret leftist society in Brussels called The League of the Just, which was by no means a self-congratulatory outfit at all. They realized they weren’t going to bring about the revolution of the workers in secret, and that they’d have to openly form a political party if they were going to get anywhere. And in 1848 that’s what they did, changing their name to the Communist League and publishing Marx and Engels’ best-known work The Communist Manifesto. Its aims were modest; just worldwide revolution to replace governments and bourgeois capitalist society with a socialist utopia.

At the time, though, in most of Europe there wasn’t all that well-established a bourgoisie. The real power in most of these countries was with the aristocracy, and the aristocrats treated the bourgeoisie like dirt when they weren’t trying to borrow money from them. Marx didn’t actually know what the hell he was talking about.

And to this end, Marx spent a third of an inheritance from his father which his uncle had withheld from a decade buying weapons for Belgian workers to kill government officials with. It being 1848, after all, and Europe being engulfed in revolutions and uprisings.

And when the Belgian government found out about that, Marx was moving again, this time to Cologne after a short stint in Paris where the Communist League’s new international headquarters had been set up. In Cologne, he began distributing handbills titled Demands of the Communist Party in Germany, which called for the bourgeoisie to overthrow the nobility so as to allow the German proletariat to overthrow the bourgeoisie and therefore remedy the fact that his revolutionary prophecies were more or less nonsense as applied to his native country.

Strangely, the bourgeoisie wasn’t roused by Communist Party demands that they kill the aristocrats and make it possible for the proles to kill them in turn.

He used the rest of his inheritance to start a newspaper in Cologne, the Neue Rheinische Zeitung, or New Rhineland News. This did a little better than the Old Rhineland News, but not much. Marx found himself beset with various police charges and spent a lot of time in court fighting off prosecution. Finally, a few months later, the paper he’d plowed his family’s fortune into ran afoul of the new reactionary Prussian government and the cops shut him down. As a special bonus, Marx was told he was welcome to leave the country at any time of his leisure so long as it was immediately.

So he went back to Paris, which was in the middle of a reactionary counter-revolution and a cholera epidemic, and it wasn’t like anybody had much time for a newspaperman who kept pissing off the wrong people and getting canceled when he wasn’t spending his family’s money playing Santa Claus to the violent proletarian vanguard.

That’s not an opinion. The local authorities informed him of that very assessment when they told him quite snootily to get the hell out.

So now it was off to London, and Marx’s wife Jenny was now pregnant with their fourth child. One might imagine that Mrs. Marx had become a bit exasperated with her husband at this point, and evidence for such an assumption can be found in what happened next.

Which was that the Communist League had settled on London as its third international headquarters in less than a year. And no sooner had that happened then many of its members declared it was time to launch the international proletariat revolution Marx had been writing about for the better part of a decade.

Marx said no.

In one of the more lucid moments of his life he assessed that a spontaneous revolution in which the workers of the world would unite to crush the capitalist bourgeoisie might actually be a disaster and the revolutionaries would just get rounded up and imprisoned or shot. And that when this happened it would be a good bet that the Communist League and all of its members probably would face more negative consequences than getting run out of yet another European capital.

Marx said that changes in society are not achieved overnight through the efforts and will power of a handful of men, and that the magic formula was scientific analysis of economic conditions of society and moving toward revolution through different stages of social development. That the ticket was to get the proletariat together with the bourgeoisie to smash the nobility, and then once that was done the proletariat would be ready to smash the bourgeoisie.

I’ll boil this down: Marx was now in London where you had to do more than make fun of German potentates and write boozy screeds attacking governments for screwing over the workin’ man to get your publication shut down. And Marx noticed there were a whole lot of indolent sons of wealthy, productive men hanging around, all of whom could be marks for the big grift he needed to run for a while. That meant that, probably to get his exhausted wife off his back, he wanted to lay low and chisel some change off the swells for a while.

He’d found the Big Rock Candy Mountain, and he wasn’t coming down off it in the short run.

So the Communist League ended up splitting in half, with the hard-core revolutionaries heading off to plan Marx’s revolution without Marx. And Marx himself was now working on something called the German Workers’ Educational Society. By September of 1850, though, the educated German workers were calling Marx a sellout for not putting his money where his mouth was and kicking off his revolution, and he resigned from that organization.

How was Marx making a living at this point? He wasn’t. He was mooching off Engels, who was himself mooching off his wealthy industrialist father. Marx managed to get a few writing gigs here and there, and then in 1852 the New York Daily Tribune, published by the famous newspaperman Horace Greeley, hired him as its European correspondent. All of a sudden Karl Marx’s goofy revolutionary theories that he’d neglected to put into force when his followers had asked him to were appearing in the pages of the world’s most widely-circulated periodical. He wasn’t getting rich, but at least he could tell Jenny that he was working at a job.

When that was plausible that is, because Marx was known by all in his acquaintance as a quite impressive drunk whose liver was, let’s say, problematic from his first stint in Paris onward.

In 1852 Marx published a theoretical work about the French revolution of 1848, which wasn’t exactly a hot seller.

By this point it should have been somewhat clear that history wasn’t really playing out the way Marx had theorized and that maybe his theories weren’t the most accurate. But since he had a meal ticket in Engels making sure he had three hots, a cot and a roof over his family’s heads, there was no particular reason for Marx to endure that reckoning. And since the British government at the time didn’t see much reason why Marx was any kind of existential threat, he was living a fat and happy life by his standards.

The severe economic consequences of the Civil War did some damage to the Daily Tribune’s finances and the readers were not surprisingly less interested in European affairs, and Marx found himself laid off in 1862. Some of the contacts he’d made at the paper, however, including the impresario George Ripley, had begun an encyclopedia and hired Marx and Engels to contribute articles to it. Engels contributed 51, Marx 16. Marx managed a minor commercial success in 1859 when he published A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, which sold out and was appraised as a critical success. He intended it to be the first installment of Das Kapital, which was to be his masterpiece of economic theory.

Advertisement

In 1864 he got involved in another revolutionary cabal, this one called the International Workingmen’s Association, which was later known as the First International. Shortly thereafter Marx found himself in another internal struggle, this one with the Russian communist Mikhail Bakunin, over how to effect the great proletarian revolution which wasn’t generating as much buzz as everybody had hoped. But his writing career took off at that point; in 1867 he published the first part of Das Kapital, and it was a sizable commercial success. People were actually beginning to listen to Karl Marx. It was almost as though capitalism was treating him pretty well and maybe he could have been grateful.

And meanwhile in 1870, an actual communist revolution broke out in Paris. But the Paris Commune was a singular failure on basically every front, particularly given the chaos and starvation it inflicted on the poor saps who were sucked into it. In only two months the French government had gotten its act together and lustily slaughtered the revolutionaries while returning Paris to market economics and regular order.

Marx wrote and distributed a pamphlet entitled The Civil War in France, essentially saying the Paris Commune was awesome and it should have been given more of a chance.

What about the second and third volumes of Das Kapital? Yeah, about those: Marx tinkered with manuscripts of both until his death in 1883 but he didn’t publish them. It was Engels who did that, publishing the second volume in 1893 and the third volume in 1894. Essentially, he was recouping the cash he spent propping up Marx for all those decades.

And in the last decade of Marx’s life, when he was in his more lucid and sober moments he spent a lot of time writing letters back and forth to other socialist revolutionaries, offering theories on how, for example, Russian farm communes could be the basis of a socialist revolution there. It’s funny, because when the Russian communist revolution did come in 1917 and that very idea was tried, half the country nearly starved to death.

Nobody ever seemed to recognize that “Hey, this stuff we keep theorizing about doesn’t really seem to work all that well.” Well, that’s not true – the vast majority of the proletariat in all these European countries got that, and an even larger share of the bourgeoisie did. At least, those of the bourgeoisie who, unlike Engels, didn’t just have a bunch of family money they could live off of while supplying sinecures to their leech friends.

Marxism is, and always has been, most popular with indolent rich dilettantes who don’t anticipate the consequences of applied Marxism. In America, there have always been an ample supply of those, as we have lots of families which can attain sizable fortunes.

So does Europe. But there’s a difference. In Europe, most of the rich families, particularly prior to the destruction of the Ancien Regime in World War I, came as landed nobility and were essentially government-sanctioned elites. Whereas in America an interesting saying came to the fore: Shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves in three generations.

We don’t use that one much anymore, as it’s less true than it used to be. But it’s still valid. What it means is the first generation of an upwardly mobile family will achieve a fortune by hard work. The second generation, born to the privilege of the first’s upward struggle, is a little softer, and probably spends down some of that fortune.

And the third generation will piss away the rest and end up broke and working-class.

You can’t take that literally, necessarily, but it does have something valid to say about social mobility in a free society – namely, that it’s based on productivity and attitude. If you don’t have those, it doesn’t matter how much privilege you were born into; it isn’t going to end well.

We’ve always understood that in America, and that insulated us from Marxism taking much hold here. In a society like ours, gobbledygook like this, from Das Kapital, generally gets laughed at:

The capitalist maintains his rights as a purchaser when he tries to make the working-day as long as possible, and to make, whenever possible, two working-days out of one.

On the other hand…the laborer maintains his right as seller when he wishes to reduce the working-day to one of definite normal duration.

There is here, therefore, an antinomy, right against right, both equally bearing the seal of the law of exchanges.

Between equal rights force decides. Hence is it that in the history of capitalist production, the determination of what is a working-day, presents itself as the result of a struggle, a struggle between collective capital, i.e., the class of capitalists, and collective labour, i.e., the working-class.

I discovered that passage back in 2012 when an Obama administration official named Rick Bookstaber, who served on something called the Financial Stability Oversight Council, had created a minor disturbance when he posted it on his personal blog.

And it’s fundamentally idiotic, because it misses a crucial part of the economic equation. Namely, that the laborer can most of the time find another job. Marx thinks capitalism is slavery because there is this binary between labor and management, but he totally disregards that an economy isn’t linear; it’s three-dimensional.

Marxists refuse to understand all this. Instead they gravitate toward institutions in which these dynamics don’t come off as quite so stupid. In each of them – government bureaucracies, Hollywood, public schools, higher education and so on – there is a distinct hierarchy which looks a lot like a pyramid and fits a Marxist analytical model.

But the local construction industry, for example, doesn’t work like that. If you’re a roofer, you might well find yourself in demand from four different homebuilders, and you can play them off against each other and choose to work for the one who offers the best compensation and work conditions. The idea you’re the proletariat and what’s in your interest is to shoot the homebuilders dead and take over their businesses so you can run them as part of a committee and get a small, but equal, share of the proceeds….

Well, let’s just say most roofers would react to such lofty, if bloodsoaked, utopianism by saying, “Why the hell would I want to do that?”

Marxism has universally failed for that very reason, and it’s no surprise that every Marxist state ultimately resorts to lies and terror as a means of keeping control of the population.

Karl Marx was a loser and a leech in life, whose writings were generally regarded as a parlor curiosity among the rich and comfortable. Not only that, he was an absolutely incurable asshole. As his biographer Werner Blumenberg wrote of his personality:

“The illness emphasised certain traits in his character. He argued cuttingly, his biting satire did not shrink at insults, and his expressions could be rude and cruel. Though in general Marx had blind faith in his closest friends, nevertheless he himself complained that he was sometimes too mistrustful and unjust even to them. His verdicts, not only about enemies but even about friends, were sometimes so harsh that even less sensitive people would take offence … There must have been few whom he did not criticize like this … not even Engels was an exception.”

His liver condition contributed to another affliction; namely, Marx was covered with boils, which were so bad that he could hardly sit down. He was this dirty, drunk, unkempt, hairy ogre who hung around the library at the British Museum smoking cheap cigars and biting people’s heads off for speaking to him. And somehow he won friends and influenced people with a philosophy which brought us Venezuelan dumpster-divers and North Koreans executed in the streets for listening to K-Pop on the radio.

But after his death when others with an investment in making him into something he wasn’t began promoting him, he went from the mid 19th century version of Bernie Sanders to the spiritual founder of an ideology which has killed well more than 100 million people and subjected literally billions of our fellow human beings to unfathomable suffering and misery under the thumb of the cruelest, most brutal murderous regimes the world has ever known.

Someday, hopefully, that biopic will be made, and when it is it ought to be utterly savage in its portrayal. If it does come out, buy tickets and take the whole family. Twice.

Advertisement

Advertisement