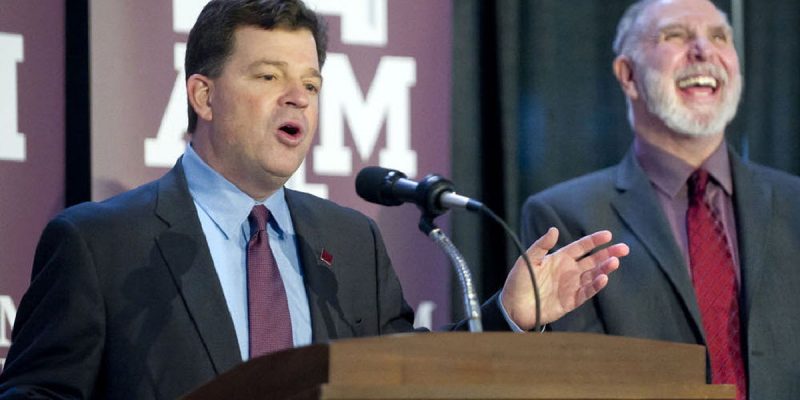

Apparently Tuesday will be new LSU athletic director Scott Woodward’s first day on the job after agreeing Wednesday to take over for the “reassigned” Joe Alleva. Woodward, a Baton Rouge native and Catholic High graduate who never left his Louisiana roots – he has a year-old membership at Baton Rouge Country Club, a fishing camp in Grand Isle and an apartment in the French Quarter, all purchased while he was living out of state with stints as AD at Washington and Texas A&M, is probably the most high-profile hire as an athletic director in LSU’s history, and fans have been thinking big since he agreed to take over his dream job two days ago.

Here are four things those fans are expecting to see him work on, and we’d be surprised if Woodward doesn’t address them very quickly.

Big Changes To The LSU Compliance Department

Talk to most coaches in LSU’s athletic programs and the one thing they’ll tell you drives them crazy about working at LSU is the ferocious nature of the NCAA compliance department. One told us not long ago “At other places, the compliance people usually tell you ‘Here’s how you do this and keep it within the rules.’ At LSU, they tell you you can’t do it, and then they self-report it to the NCAA. It’s a major disadvantage.”

So far, the results of that coach-unfriendly approach has generally kept LSU from being hit with any major NCAA probation, at least while Alleva was the athletic director – though LSU’s self-reporting to the college sports governing body has spun off a few seemingly needless minor penalties which did make a difference. For example, NFL All-Pro defensive tackle Akieem Hicks was once an LSU signee, but after Hicks signed with LSU out of a junior college in California he got a ride from the airport and a place to stay for the weekend on an unofficial visit from a recruiting hostess with whom he’d struck up a relationship – and that rather innocuous NCAA violation ended up costing Hicks a chance to play at LSU. He ended up at the University of Regina in Canada before being drafted in the 3rd round by the Saints and launching an NFL career. Meanwhile LSU lacked a monster interior defensive lineman to stop the run, something which may have cost the Tigers a shot at a national championship in 2010.

LSU’s more-stringent drug testing policy has also put the school at a competitive disadvantage to other SEC programs, something coaches in football and basketball have been vociferous about changing.

The compliance department, headed by Bo Bahnsen, is likely going to be the thing every coach Woodward visits with brings up as something which has to be overhauled with an eye toward cooperation rather than punishment. Bahnsen might not be gone, but he’s surely going to be reined in. And Miriam Segar, who is the associate AD for the non-revenue sports and used to have Bahnsen’s job – she was an influencer during Alleva’s time consulted with on compliance issues – will definitely have her wings clipped, if not more.

Nikki Fargas’ Life Is About To Change

LSU’s women’s basketball program was, not all that long ago, on a similar level to Connecticut and Tennessee, the giants of the game. The Lady Tigers went to five straight Final Fours, though they never quite could get over the hump and win a national title.

All that is gone now. This year the program posted a 16-13 record, just 7-9 in SEC play, and turned down a bid to the women’s National Invitational Tournament. Meanwhile, former Lady Tiger Chloe Jackson, who had been the leading scorer on LSU’s 2017-18 team, won a national championship playing for Kim Mulkey at Baylor as a graduate transfer.

Nikki Fargas has been the coach of the Lady Tiger team since 2011. She hasn’t made it out of the first round of the NCAA tournament since 2014. Fargas’ work ethic has been a major concern for quite some time – there was a good deal of buzz early in her career over the fact she decamped for Los Angeles at the end of her team’s season and didn’t return until school started in August for the first couple of years at LSU. That isn’t the case anymore but recruiting is clearly deficient on this team and LSU has an alarming number of players transfer every year.

There is an obvious solution to the women’s basketball program issue, which is to move Fargas out and Mulkey in. Mulkey is a Louisiana native, whose hometown of Tickfaw is less than an hour from the LSU campus, and a legendary player at Louisiana Tech. Her son Kramer Robertson was a star shortstop on LSU baseball’s 2017 national runner-up team, and she was in the stands at Alex Box Stadium watching him play for the majority of the four years Robertson was a Tiger – so much so that the constant live shots of Mulkey in the stands by SEC Network and ESPN cameras became a running joke among Tiger fans.

The only real obstacle to hiring Mulkey to build a national championship women’s program at LSU is money. She makes $2 million per year at Baylor, which is a lot more than the $750,000 LSU is paying Fargas. But this year LSU averaged 2,100 fans per game in the 13,000-seat Pete Maravich Assembly Center for Fargas’ unranked and unremarkable team, and when the program was going to those Final Fours it frequently averaged four or five times that many. Figure $12 in revenue per additional paying customer, whether in ticket sales, TAF seat-license donations or concession sales, over 18 home games per season (not counting potential sales for NCAA Regionals LSU could host) over, say, 8,000 more fans in the seats for a nationally-competitive team, and you’re looking at 8,000 x $12 x 18 = $1,728,000 in revenue being lost due to an empty arena and a bad program. Add that number to Fargas’ $750,000 salary and you realize that LSU could pay a women’s basketball coach with the cache’ – especially locally – of a Mulkey to $2.5 million a year and justify the investment even before seeing spinoff benefits.

Like, for example, the fact LSU is in the middle of a $1.5 billion capital raise, $600 million of which is supposed to come from the Tiger Athletic Foundation. Who do you think is better poised to help the university achieve that goal – Fargas, whose work ethic is questionable and who appears to be on the way out as the women’s basketball coach anyway, or Mulkey, a Louisiana legend whose arrival in Baton Rouge would be the biggest splash of a head coaching hire maybe in school history (which might sound strange given we’re talking about women’s basketball, but think about it – when has LSU ever hired a national champion head coach at the top of his or her game in any sport?)? The guess is Mulkeyn would more than pay for herself.

When Alleva was the athletic director at LSU it would have been considered fantasy to land Mulkey as the women’s basketball coach. Not with Woodward. He’s the guy who lured Jimbo Fisher away from Florida State with a 10-year, $75 million contract to take over as Texas A&M’s football coach, and that was after landing Chris Peterson as the football coach at Washington when it was thought Peterson would never leave Boise State. And Woodward just a couple of weeks ago poached Buzz Williams to coach basketball at Texas A&M with a six-year contract starting at $3.8 million per year (it escalates to $4.4 million in its final year). Splash hires for big dollars are Woodward’s stock in trade, and Mulkey is an obvious call.

It’s not even too late for Woodward to make that move immediately in advance of next season, though typically the new athletic director will give a coach a year on the hot seat before making a change. Either way, Fargas is on notice that life is about to be very different.

LSU Football’s Gameday Experience Needs Work

One of the things which turned LSU fans against Alleva even before the various public-relations messes he kept getting himself in was the perceived deterioration of the Tiger Stadium atmosphere, something which generates larger and larger complaints from the fans all of the time.

There are a host of issues which need to be addressed there, and they have to be addressed because physical attendance at college football games is a problem across the country. You can buy a 60-inch TV at Target or Wal-Mart for under $600, which is a good bit less than season tickets to LSU football games will cost, and watch every single LSU game on that TV without worrying about parking, traffic, bad weather, drunken idiots in your section, bad food at the concession stand or any of the other inconveniences common to watching athletic events. In other words, the bar has been raised – and LSU football doesn’t just sell itself like it used to.

Which means you’ve got to make that gameday experience special. And while Alleva certainly made moves in an attempt to keep up, those never really worked. The piped-in music at Tiger Stadium has been a source of irritation for not just the older fans who don’t particularly care for the newer fare, the video boards around the stadium are certainly striking but offer far too much advertising and not enough content to add to the experience, nothing has ever been done about parking and traffic – which is almost criminal seeing as though there is the same capacity for ingress and egress to that stadium at 102,000 seats that there was when it had 80,000 seats – and the newest feature to the stadium, a beer garden under the South End Zone seats called The Chute, actually pulls fans out of the stands during the game which makes the perceived problem of no-shows even worse. Attempts to improve the concessions in the stadium have been, sadly, unsuccessful (to put it kindly).

Advertisement

Woodward grew up in Tiger Stadium, so you’d think he would have a grasp on what made the place special in the first place and how to inject that magic back into the facility and the gameday experience. Some of what would really help is a bit beyond the athletic director’s grasp – a parking garage close to the stadium, for example, with good road access, and perhaps more lanes on Nicholson Drive or River Road. But a lot of it is little changes to be more responsive to the fans.

Paul Mainieri Needs Help – Even If He Doesn’t Want It

Let’s not put too fine a point on this: LSU’s baseball team, which opened the season as the No. 1 team in the country, is currently a mess.

A lot of things beyond head coach Paul Mainieri’s control have led the Tigers to where they are – currently 24-15 after taking an ugly 16-9 beating last night in a home game against unranked Florida. There has been a flurry of injuries to key players, and LSU might have a better pitching staff among hurlers not able to play, at least on paper, than among the healthy ones. What’s more, Mainieri’s father died a few weeks ago, and it’s clear he’s carrying a heavy heart around as a result – the two were very close, and Demi Mainieri’s passage is a devastating personal loss for Paul which understandably distracts him.

And the season isn’t over, though expectations of a turnaround are dimming. Some of those injuries will heal and LSU will get to something close to full strength before the end of the season. A late run isn’t impossible.

But there are limits to how far this team can go, and those limits are Mainieri’s responsibility. For example, LSU doesn’t have a single healthy left-handed pitcher on the roster – Easton McMurray is the only one listed, and he’s out for the year. Not to have four or five is a glaring error in roster management, and that’s a gaffe by Mainieri and recruiting coordinator Nolan Cain which can’t be excused. Nor is LSU’s complete dearth of talent behind the plate – these are the worst catchers anybody can remember seeing on an LSU team, both defensively and offensively. Not to mention Zack Watson is the only productive right-handed hitter LSU has, something which might change when freshman infielder Gavin Dugas is healthy in a couple of weeks. Dugas might fix something else which is obvious; namely that LSU is playing two second basemen who offer almost nothing offensively. There are major, fatal flaws to this team which don’t make sense for an elite program like LSU to have.

And then there is the lack of a true hitting coach. Volunteer coach and former LSU player Sean Ochinko has that job, and he’s in his second year doing it, but Ochinko had never been a college baseball coach before Mainieri brought him on staff – and as the hitting coach Ochinko isn’t really doing so well. LSU’s hitters strike out with blinding regularity, and there are far too many easy outs and protracted slumps in this lineup. LSU hasn’t had a paid hitting coach since Andy Cannizaro left for the head coaching job at Mississippi State in December of 2016, and it’s clear the current arrangement doesn’t work.

Today there will be a vote by the NCAA on adding a third paid assistant coach for baseball and softball. If that passes, Mainieri won’t have an excuse not to go out and get the best hitting coach in the country. But even if it doesn’t, Woodward needs to do what Alleva should have done – namely to sit Mainieri down at the end of the season and say “Paul, let me buy you the best hitting coach in America, so we can get you that second national championship ring you deserve.”

And if Mainieri resists, the response needs to be “That wasn’t a request, Paul.”

Cain is occupying the spot that on most programs would go to a hitting coach. He had the No. 1 ranked recruiting class in the country this year, though there are a lot of disappointments among members of that class so far. If a third paid assistant isn’t in the cards per the proposed rule change, then it’s time for the athletic director to step up and create a plan which allows Cain to be a volunteer coach who makes adequate money in other ways – as an assistant athletic director in charge of camps, or something. At this point the hitting coach issue has to be addressed, period. It’s no longer optional.

The fans, particularly after last night, are increasingly screaming for Mainieri’s head. That’s an overreaction to a season where adversity has become overwhelming. But there is no doubt Mainieri is beginning to get a bit stale as the baseball coach at LSU and it needs to be addressed. He needs an injection of energy, new ideas and new approaches, something a high-profile assistant hire from another successful program can provide. Having all of his coaches save for pitching coach Alan Dunn (who’s in his eighth year and might be stale himself) be former players who have never coached anywhere else means that staff is essentially an echo chamber, and it’s not working. A good athletic director can provide some adult supervision and get Mainieri back on track like he was when he had six straight teams finish as national top-8 seeds from 2012-17 – and maybe even send him out as a national champion.

Because Mainieri isn’t long for this job. He’s only got one or two more years left before he hangs it up as a baseball coach. Rather than having that time left here be a cacophony of screaming and recriminations from frustrated fans, proper management indicates the thing to do is to help the coach with the resources he needs to go out a winner.

Advertisement

Advertisement