While we take a break from debates over fried chicken philanthropy and whether world leaders doing their thing over the phone constitutes impeachable offenses, we pause for a moment to be thankful.

As a nation we’re arguably more politically, culturally, and religiously divided than ever before. It is not easy to solve around the family dinner table how to be thankful. Or to Whom we are thankful.

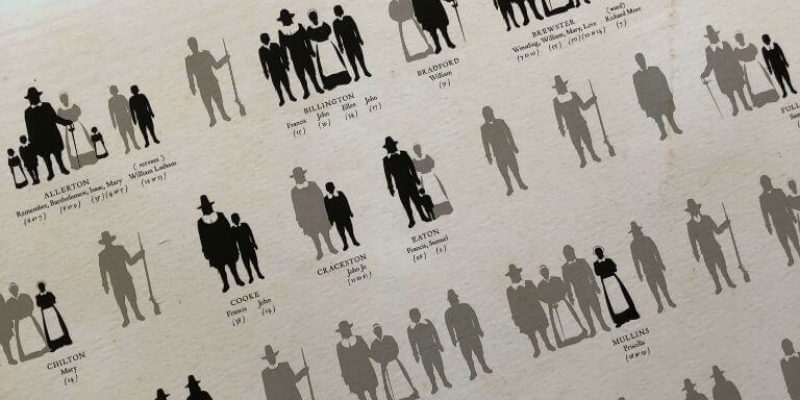

This time of year, many articles address this existential Thanksgiving crisis by reminding us of the often-neglected story of the Pilgrims of Plymouth Plantation who at first tried collectivism as a means of building a utopia in the New World — only to realize that individual incentive is the best way forward. You know the story: the native Americans who lived closer to the natural elements than European civilization allowed (45 of the 102 Plymouth settlers died in the winter of 1620) traded benefits and survival skills with the settlers. Together, they better averted disastrous conditions and were thankful to God despite their many differences. That is what we consider to be the first Thanksgiving, though it was formally established through proclamations in the centuries to follow.

As for the Pilgrims, they paved the road for our constitutional republic by learning the hard way …

In the diary of the colony’s first governor, William Bradford, we can read about the settlers’ initial arrangement: Land was held in common. Crops were brought to a common storehouse and distributed equally. For two years, every person had to work for everybody else (the community), not for themselves as individuals or families. Did they live happily ever after in this socialist utopia?

Hardly. The “common property” approach killed off about half the settlers. Governor Bradford recorded in his diary that everybody was happy to claim their equal share of production, but production only shrank. Slackers showed up late for work in the fields, and the hard workers resented it. It’s called “human nature.”

The disincentives of the socialist scheme bred impoverishment and conflict until, facing starvation and extinction, Bradford altered the system. He divided common property into private plots, and the new owners could produce what they wanted and then keep or trade it freely.

Communal socialist failure was transformed into private property/capitalist success, something that’s happened so often historically it’s almost monotonous. The “people over profits” mentality produced fewer people until profit—earned as a result of one’s care for his own property and his desire for improvement—saved the people.

[…] When God instilled a measure of peaceful, productive self-interest into the human mind, he knew what he was doing.

Read the rest of Foundation for Economic Education’s President Emeritus Lawrence W. Reed‘s analysis here. It’s quite good.

Reed’s final thought brings up the spiritual dimension of Thanksgiving: that it’s not man-made schemes of equity or social justice that we’re grateful toward, but God himself as the source of all blessings. Meagan Hill writes for The Gospel Coalition:

Advertisement

… Gratitude isn’t just contented mindfulness. True gratitude is directed at our God, the giver of every good and perfect gift (James 1:17). In expressions of thankfulness, we exalt him, proclaim his faithfulness, and confess we have nothing apart from him. It’s especially fitting, then, that we should do this together.

For those on the secular left, gratitude can often be a mental exercise of taking inventory of the positive things in one’s life and wishing that some system of social activism or government would make sure everyone else gets to have those nice things, as well. As we progress, a certain sense of guilt can nag us into throwing away individual incentive for something akin to Socialism.

For those closer to the right side of the spectrum, Thanksgiving takes on something closer to its original meaning: a realization that this world is a fallen place and yet God still loves us enough to allow us to work to improve our conditions. We also find that as we work to improve our lot we become, as a result, more grateful (read: less entitled).

Thanksgiving is a community celebration, in that as individuals who have an incentive (and a God-given order to work and “be fruitful and multiply) we can come together and see how God has worked in each one of us, to restore us to what he originally had in mind. If Thanksgiving is viewed through a collectivist lens, the holiday loses so much of of its meaning.

Hill continues …

Public thanksgiving allows others to “hear and be glad” and encourages them to corporate praise. As we sit around the Thanksgiving table with family and hear their words of thanks to God, it reminds us that we, too, ought to be thankful for the same mercies.

On our own, we are often slow to gratitude, but public thanksgiving keeps us from drifting into the ways of the godless who do “not honor him as God or give thanks to him” (Romans 1:21). The company of others helps us recall just how much we’ve received.

Before we return to beating back creeping socialism on Black Friday (whether by political action or our own consumer activity), let’s take a moment today and re-orient our own thinking so we do not end up missing the whole point of this business of giving-thanks. We might even be able to reverse our long march toward socialism.

Advertisement

Advertisement